The post LiisBeth Dispatch #32 appeared first on LiisBeth.

]]>

VIEWPOINT

The Day Hillary Came to Town

Over 5,000 Canadian men and women, plus strong representation from Democrats Abroad came together on Sept. 28 at Exhibition Place in Toronto to hear Hillary Clinton talk about “What Really Happened” (also the title of her new book). The book tour based event started on a weird note with a 15-minute live musical performance by a tenor. But setting that aside, Clinton pleased the crowd, delivering inspiring one-liners, including “I’ve been called many things, but quitter is not one of them!” and “The only way to get sexism out of politics is to get more women into politics.” Each was followed by deafening cheers of support.

The crowd became more subdued as Clinton revealed new details about Russian election interference via twitter bots and artificial intelligence (AI) to help spread false news. What we have learned from this past election, she argued, other than that America is still not ready for a woman President, is that false news is now the most clear and present danger to our democracy — a system that depends on a well-informed citizenry.

And Clinton is right to have emphasized this point. AI is serious business.

Vinod Khosla, a 62-year-old billionaire American-Indian engineer and venture capitalist who now writes a popular blog on tech trends, told the 5000+ audience at Elevate Toronto on September 12 that the new weapon of mass destruction in the digital world will be AI. All nations are working hard to master its power. To bring the point home, Khosla reminded everyone that Russian President Vladimir Putin recently said, “Artificial intelligence is the future, not only for Russia, but for all humankind. It comes with colossal opportunities, but also threats that are difficult to predict. Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.”

That used to be said of nuclear bomb technology.

Last week, Gartner, a reputable American research and advisory firm providing information technology-related insight for business leaders, published its latest future trends report. It predicts that “By 2022, most people in mature economies will consume more false information than true information” and that in three years from now, “AI-driven creation of ‘counterfeit reality’ or fake content will outpace AI’s ability to detect it”. The forecaster also predicts that 50% of companies will be spending more per annum on bots and chatbot creations than traditional mobile apps.

Here at LiisBeth, we have written about how AI science, stewarded by men at this point, has serious gender implications to consider. Imagine a world where patriarchal responses to “If this, then ____”-based algorithms are so deeply encoded in systems of life on this planet that systemic issues they inadvertently create they might never be reversible. Microsoft’s Tay, the twitter bot that became so misogynistic and racist after 24 hours of “learning” from humans that it had to be quickly unplugged and put down before more damage could be done, is a good example. Luckily, Tay, considered an AI “toy”, was not driving cars or deciding who would be scheduled for work next week.

AI can make lives easier, reduce costs, and the technorati say it might create more jobs than it eliminates in the long run. But at what cost?

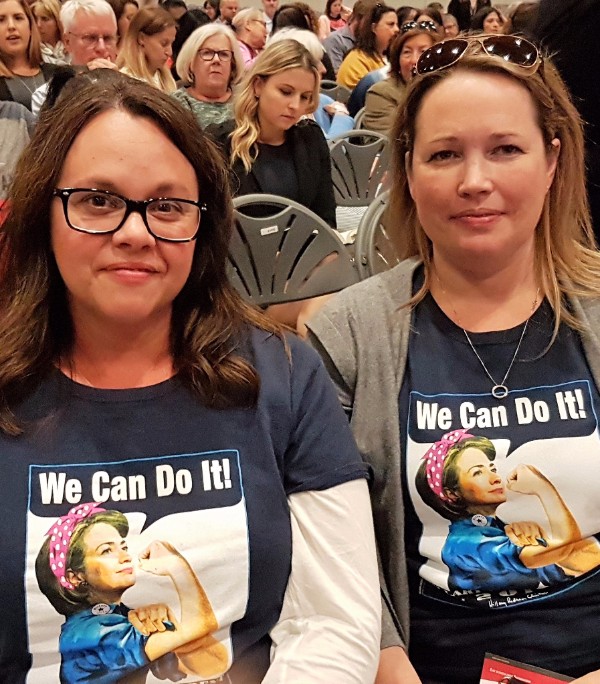

Back at the Clinton event, LiisBeth spoke with attendees Pamela Librasso and Sara Vause to find out why they were there. Both spoke about being awed by Clinton’s incredible career, her long-standing commitment to advancing women, and their deeply felt disappointment at the outcome (and continuing fallout from) the results of the U.S. election.

Librasso was so jacked up about Clinton potentially winning the election she flew down to be part of her last campaign rally… and she is a Canadian!

“Anyone who said her being a woman had nothing to do with her losing is absolutely wrong,” said Vause.

Clinton adds that anyone who believes false news spread by early-stage AI on social media in the form of twitter bots had nothing to do with it, is equally wrong.

The ongoing post-election inquiry by the U.S. House and Senate intelligence committees reveals disturbing facts that support Clinton’s views.

Most of the people attending the Clinton event were there to show their support and appreciation for this intelligent, fearless woman (no matter what your opinion of her politically might be) who built and earned an amazing, and not over yet, career.

Most left feeling that they just experienced another important wake-up call regarding AI.

Feminist thought leaders need to get serious about amping up their interrogation of this emerging technology. To quote Clinton, we need to “resist, persist, insist and enlist” to ensure we continue to advance gender equality, especially in a AI-weaponized world.

THIS WEEK ON LIISBETH

When a Catalyst Becomes an Inhibitor

There have already been a lot of news stories written about women’s advocacy organization Catalyst Canada’s recent decision to appoint yet another male bank CEO as the organization’s Chair of the Board. But we felt the need to weigh in too. Spoiler alert: It’s not just the optics that we need to consider. Find out more here.

Want Change? Put a Woman in a Ring on It! Part II

This week on LiisBeth, we publish part two of Savoy “Kapow” Howe’s story where she talks about running a trans-inclusive enterprise and her experience working with people with disabilities in the boxing ring.

Howe is the founder of the Toronto Newsgirls Boxing Club. On the subject of why we still need women-centred spaces, she says “I noticed that once I took my club out of a co-ed space we were renting, the women became, well, bigger. They took up more room. And became more of themselves.” Check out part one of her story here. Part two can be found here.

LIISBETH FIELD NOTES

Sheldon Levy on Advancing Women in Entrepreneurship

Sheldon Levy is a man of great accomplishment. His impact on Ryerson University and the city of Toronto is legendary. The Ontario Deputy Minister of Advanced Education and Skills Development (until Nov. 1) is the co-founder (along with Valerie Fox) of the top incubator in North America, the DMZ. He is the former president of Ryerson University. And he was recently named the new CEO of Next Canada, a startup incubator at the University of Toronto — one not known for the gender balance of its participants, mentors, lecturers or board.

LiisBeth had a chance to speak with Levy about what he thinks is necessary to increase the number of women participating in Canada’s accelerator and incubator spaces, including the one he now leads.

His answer: Change the climate, not the individual. He adds that based on his own observations, and to his dismay, many of these male-dominated environments are “not fun for women”. He added “We are not being honest about what the problem is.”

Hiding from this truth could be a contributing factor behind poor gender balance outcomes in incubator and accelerator spaces across Ontario. Even for Ryerson’s celebrated digital media zone, the data shows that women-led companies at DMZ currently add up to about 16% of all companies working in the 70 000 sq ft space. When you expand the count to include ALL women working in any role, in any startup, it increases to approximately 30%.

Liisbeth went on to ask Levy if he was a feminist. Levy replied, bemused, “I have not thought about it. I guess I would say I am just a person with my eyes open.”

Let’s see if having one’s eyes open is enough to make a dent in the previously reported on gender bias issues at Next Canada.

What’s the EFF?

We know that systemic barriers prevent the majority of people on the planet from participating fully in life on the planet, and from determining our collective future.

So what’s the good news?

In fact, today’s fast-growing number of entrepreneurial feminists are leading some of the most exciting transformations in our communities, the economy — and more importantly — our minds. It was time to bring them together as a community.

At this inaugural Entrepreneurial Feminist Forum, we will be connecting, exploring and learning about diverse feminist approaches to business design, product and service innovation, alternative success strategies, feminist metrics, and much more. The forum is designed as a feminist, inclusive event and features a lot of doing, not just talking!

Confirmed speakers already include Dori Tunstall, Dean of Design at OCAD University, Dr. Barbara Orser, University of Ottawa Professor and co-author of Feminine Capital, CV Harquail, PhD, Stephen M. Ross School of Business (NJ) Professor and Co-founder of Feminists at work, Kelly Diels, feminist marketing consultant and author plus many more who will be announced in the coming weeks!

We are still open for workshop proposals until Oct. 15. Check out the guidelines here.

Don’t miss this opportunity to learn about new tools, ideas, share your work, identify future collaboration opportunities, become inspired, and find out more about entrepreneurial feminism as a force for change.

Early bird tickets at $99 are limited ($125 per person afterward). Get them while you can. Here. Now! For more information visit www.feministforms.com. For those for whom price or any aspect of the event is a barrier please send us an email and we will find a way to accommodate! If you have questions, email [email protected].

Whoa! Canada’s First Women’s Chamber of Commerce?

Did you know that Women’s Chambers of Commerce organizations exist in many countries across the globe, except Canada?

Well, that’s about to change.

Last week, Heather Gamble, founder of Women on the Move, announced the creation of Canada’s first Women’s Chamber of Commerce. The new Chamber, due to launch officially on November 30th, will provide resources and advocate on behalf of women entrepreneurs in Ontario.

Ontario is the Canadian province without a Women’s Enterprise Centre.

If you would like to learn more about this initiative or want to become involved, consider attending their October 12 information session (this Thursday) from 6:30-8:30pm at Women on the Move, 2111 Dundas Street West, Toronto. To RSVP, click here.

Eve-Volution Inc. is Recognized as a Best For the World B Corp!

As you may know, LiisBeth Media is a division of Eve-Volution Inc., a three-year-old B-Corp-certified consulting and educational enterprise that focuses on helping advance gender equity and inclusion in the entrepreneurship and innovation space. Eve-Volution Inc. was recently recognized as one of 2017’s “Best for the World” B Corps due to our community impact scores! If you are interested in learning more about Eve-Volution Inc., visit www.eve-volution.com.

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT?

- Can you really empower a woman in India with a chicken? Read “The Myth of Women’s Empowerment” in emerging countries here.

- We have been enjoying Bitch Magazine’s series of six long-read articles on the topic of fragility. The latest one is entitled “I didn’t know how much I needed a woman President until it didn’t happen”, by Jessica Marie Johnson. You can read it here.

- The annual B Corporation Champions Retreat was held last week for the first time, and right here in Toronto. There are now over 200 B Corps! We wanted to give a shout out to Jeff Ward, founder of Animikki, also Ojibway, Metis, Thunderclap Boy of the Bear Clan with UK settler heritage for becoming the first Indigenous-owned B Corp in the world!Can

CAN’T MISS EVENTS

- Canadian Women in STEM. Saturday, Oct. 14, 10:00 AM-4:00 PM, 200-20 Toronto St., Suite 200, Toronto, ON. Presented by HerVolution. Register here.

- Emancipate Me. Emancipate This. Tuesday, Oct. 17, 6:30 PM-7:30 PM. Authors Vivek Shraya and Lauren McKeon discuss the face of racism, the anti-feminist movement, and their latest books, Even This Page Is White and F Bomb: Dispatches on the War of Feminism, , Toronto Reference Library, Toronto, ON. Free.

- FEMM Live. Saturday, Oct. 21, Fairmont Royal York, Toronto, ON. $137-$350. Register here. Speakers/performers include Margaret Trudeau, Vicki Saunders, Amber Mac, Paulette Senior, Heidi Allen, Maria Locker, Sandra Laronde, Kelly Lovell, Stephania Varalli, Susan Howson, Joy Foster, Jessica Pheonix & more!

-

Entrepreneurial Feminist Forum. Saturday, Nov. 11, 9:00 AM-6:00 PM. 100 McCaul Street, OCAD U, Toronto. $99-$125. Only 25 early bird tickets available so act fast! Register here.

That brings us to the end of this October newsletter.

We hope you enjoyed it as well as our deeper reads at www.liisbeth.com.

If you like what you read, we humbly remind you that subscriptions are $3/month, $7/month or $10/month. We accept PayPal and credit cards. Funds go directly towards paying writers, editors, proofreaders, photo permission fees, and illustrators. LiisBeth needs your love—and financial support.

The next newsletter is scheduled for early November. In the meantime, take care of yourself. And each other. It’s been a little rough out there for many of us these past few weeks.

Petra Kassun-Mutch

Founding Publisher, LiisBeth

The post LiisBeth Dispatch #32 appeared first on LiisBeth.

]]>The post Social Enterprise in Ontario: Substance or Style? appeared first on LiisBeth.

]]>Dressed mainly in dark suits and white shirts, the participants exchanged pleasantries as they signed in, lined up for coffee, yogurt and other snacks, and then took their seats in the lecture hall. Normally, the speakers would be talking about things like trends in hedge funds, the benefits of free trade, how to do discounted cash flows, or regulatory compliance in today’s securities markets, but today, was different. Today, they were there to learn how to become social innovators or entrepreneurs in 24 hours or less.

My, how things have changed since my days in business school.

Today, most of us agree on the importance and urgency of tackling our man-made, increasingly dangerous social fissures and assaults on the environment. And the 2008 banskter led financial meltdown meant business leaders and the sector lost much of their license to operate. Trust levels were extremely low. MBA enrolments dropped. No one wanted to take a course in how to become an untrusted scourge. And prospective students were looking for degree offerings that blended doing well with doing good.

With god speed (and the drive of market forces), business schools across the country quickly increased their offering in social innovation, social enterprise, sustainability, and corporate social responsibility by creating new courses, certificates, centres, offering conferences, speaker series, and even offering majors in the subject. The business press covers these topic and puts socially progressive CEO’s and companies like founders of Etsy, Warby Parker and Patagonia on its covers. And there are several versions of hybrid business models being explored in an effort to re-define what it means to create value, wealth and good at the same time.

Clearly, the private sector is serious about making the world a better place. And it’s a good thing this sector is increasingly engaged, for it has enormous resources, including dollars, people and robust scalable systems to affect positive change – fast.

Curiously, the not for profit sector is pushing back. It doesn’t trust the private sector. And it seems concerned about defending and strengthening its own turf, as opposed to welcoming new players.

But the truth is, we probably can’t avoid inviting the private sector into the social innovation tent. Why? Because no matter how Davids are funded, they alone cannot slay an army of Goliaths coming our way.

David is Losing

Canada boasts about having the second largest not for profit sector in the world, but it still only represents less than 4% of its GDP (8.1% including Universities, Colleges and Hospitals). In Ontario, it represents 2.5% of Ontario’s GDP. In short, regardless of jurisdiction, it’s tiny in the grand scheme of things. Yet and the problems are growing, and more complex than ever before.

Statistics also show that most Canadian not for profits have been operating for more than 20 years, and collectively spend $67+ billion per year working on social and environmental issues. Yet, the needle on social and environmental betterment has hardly moved. It’s a little like trying to bring down a well-fed, destructive giant with a series of mousetraps.

Indications suggest that things are also getting worse, not better. For example,Toronto’s 2014 Vital Signs report, a civic report card released annually by the Toronto Community Foundation, points out 43 per cent of Torontonians today live in low or very-low income neighborhoods, and that this will increase to 60% by 2025. In addition, two-thirds of these are visible minorities. Poverty in Toronto is not only growing, but is also becoming increasingly racialized, compounding an already daunting issue. Not surprisingly, sector leaders are starting to wonder if the idea of tax-code based segregation of responsibilities—i.e.: leaving “doing good” work to non-profits or charities in an increasingly global world, is an outdated, relic of the industrial age.

Can the Private Sector Cope with Complexity?

As the first speaker began back at the University, students were clearly motivated and inspired by the panel of successful social innovators, but as the morning wore on, many started to also look frustrated and uncomfortable. Turns out the space is a hornet’s nest of different views, approaches and opinions on how to measure success. Leaders and thinkers in the space can’t even agree on its definition. In business school, things are simple. This is a debit, and this is a credit. If demand goes up, prices come down. Profitability is a simple arithmetic calculation. But measuring the impact of a program on a person’s life? Not so easy.

The world of social innovation is a bit like trying to interpret a Montreal Automatist abstract painting.

Definitions

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty explains his use of the word “glory” to Alice in this way: “‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.” It seems, the definition of the terms social innovation, social enterprise, or social entrepreneur is similarly in the eye of the beholder.

According to the U.S. based Stanford Social Innovation Review (SSIR), which is the equivalent of the Harvard Business Review (HBR) for the social sector, “A social innovation is a novel solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient, sustainable, or just than present solutions and for which the value created accrues primarily to society as a whole rather than private individuals.” In their view, it can be for profit, or not for profit.

However, the Social Enterprise Council of Canada says that:

“Social enterprises are businesses owned by non-profit organizations, that are directly involved in the production and/or selling of goods and services for the blended purpose of generating income and achieving social, cultural, and/or environmental aims. Social enterprises are one more tool for non-profits to use to meet their mission to contribute to healthy communities. All others are excluded.

Back here in Ontario, Ryan Locke, a Director of Social Enterprise at the OntarioMinistry of Economic Development and Innovation (MEDTE), explains his Ministry’s definition. “I am from the government.” begins Locke, “And so necessarily, we have a big tent definition for social enterprise. For us it’s about the growth opportunity. Today, there is $3-billion dollars in impact investment capital available in Canada alone. There are over 10 000 social enterprises in Ontario, one third of which are less than five years old. So to us, it doesn’t matter what it’s called, as long as it improves the economy.” In other words, again, it does not matter if it is for profit, cooperative, or not for profit. In the government’s view, all are included.

Entrepreneurs: The beach head of social change.

Today, fostering entrepreneurship and supporting entrepreneurs is generally accepted by many including all levels of government, is the answer to everything. Indeed, between federal and provincial governments alone since 2012, over $600M in public money matched by private sector money has been earmarked to support capital needs of start-ups and small businesses. Even foundations, like the McConnell foundation has entered into the fray by creating the ReCodeprogram designed to help create social innovation programs in Universities.

But do our current societal values and legal structures really support real social entrepreneurship?

The Toronto-based Centre for Social Innovation (CSI), the brain-child of Founder and now CEO, Tonya Surman, has grown from one to three Toronto locations plus one in New York City in under 10 years. The social innovation themed co-working space boasts 1600 plus individual community members and is home to over 180 organizations, 33% of which are social purpose enterprises, 35% non-profits, and 25% charities.

This makes CSI is the ideal location for the office of a specialized, social innovation focused law firm like Wakalut/Dhirani LLP. There I met Robert Wakalut, founding co-partner, is dressed in dapper dark brown corduroy suit jacket, jeans, a checkered pressed shirt and pointy dress shoes, and looks more like a fashionable professor than his Canali suit-ster colleagues on Bay Street. Sipping our coffees, sitting on a vintage couch at CSI’s Bathurst location, we talk about the social innovation and entrepreneurship space and why entrepreneurs need his help.

He tells me that the question he is often asked to address is “What legal form should my enterprise adopt”?

“A lot of times people equate social enterprise with not for profit or charity.” says Wakalut. He also notes that social entrepreneurs seem to be most enthusiastic about the not for profit, or charitable, form because they feel it serves as a type of consumer message short hand: A legal not for profit designation tells people clearly that the company is committed-in fact-required by law to do good, while a for profit designation in the “doing good” space is considered suspect. Sounds simple enough, until you consider the entrepreneur, and the fact that the legislated requirements for forming a not for profit or charity are completely antithetical to the reasons one chooses to become an entrepreneur.

I spoke with Ilana Ben-Ari, a celebrated award winning social entrepreneur and co-founder of Twenty-One Toys, a company that designs toys which encourage the development of traits like empathy, and acceptance of failure. In fact in July 2014, they partnered with Spin Master to send its award winning empathy toy to the Gaza strip/Israeli communities within the conflict zone.

No wonder it’s hard to pin her down. She works 24×7. She rarely sleeps. She travels back and forth to China, and doesn’t have two cents to rub together. She has not paid herself in years. But hopes that once day soon, that will change.

Twenty One Toys was incorporated as a for profit company. And I asked Ilana why. Ilana says “Well at first, I wanted to incorporate as a non-profit corporate because that’s what I thought a company that is out to do good in the world should be. So I phoned my mentor to ask what she thought. After she stopped laughing, she went through all the reasons why this would be a bad idea.”

Ilana wishes there was some sort of in-between option for entrepreneurs like herself.

Entrepreneurs, by nature are looking for control over their lives, and a self-determined approach to doing well for themselves and their families. They are willing to sacrifice a lot up front, but expect payback which takes into account a risk multiple, at some future point. The social entrepreneur wants the same thing, but looks to achieve this while focusing their talents and resources on solving pressing social or environmental issues.

But since you cannot own a not for profit, there will never be an exit payout, or put another way, a change to earn out what you put in at a later date. And it gets worse.

To be a not for profit means ceding control of your enterprise’s future, from the start, to an unpaid, volunteer-based Board of Directors, the members of which sets your salary and might attend meetings, if you are lucky, once a month. It means more bureaucracy and slow paced decision making in a game that requires speed and agility. It means additional reporting, legislative oversight, higher costs to incorporate, limits on how much income your enterprise can earn from commercial sources without compromising its tax exempt status, and an annual income unlikely to be higher than $62,000 gross; the average earnings of a not for profit Executive Director. Ironically, in the not for profit sector, anyone who does good cannot also do well.

Frankly, it’s a wonder anyone even tries to found a non-profit at all, unless they already have the personal financial standing to do so, which in that case, means social entrepreneurship, or founding a non-profit is a luxury endeavor for the really just the 1%, or reasonably well off people who can afford to forgo acceptable earnings, and have access to this network to fundraise.

While not for profits do terrific work, the legal form and tax code under which hit operates ensures that there is no way in hell that any entrepreneur would ever incorporate as a non-profit. At the same time, by incorporating as a for profit, the social entrepreneur has a harder time convincing consumers that their motives are truly balanced (to most consumers, non-profit status says “halo lives here”) is subject to increased difficulty in getting their message across, securing aligned capital, and the high potential of future dissolution of the mission in the blink of an eye, or in the event of a sale, leaving their stakeholders, and community in need served, suddenly stranded.

It seems that mixing entrepreneurship and non-profit or charitable legal forms is like trying to mix oil and water.

Dual Purpose Legislation-An alternative path

For many jurisdictions, the solution to the oil and water problem was the creation of a separate, hybrid legal form allowing entrepreneurs to pursue social goals while still generating a profit and providing better access to aligned capital, with a mission safeguarded by legislation, was pioneered in the United Kingdom. The Community Interest Corporation (CIC) was introduced in 2005; today, there are over 10,000 CIC’s in the UK and Scotland. Six years later, the US created the Benefit Corporate legal form. Today 30 states have adopted a Benefit Corporation legislation and several more are in the process of introducing a similar form within the next two years. In March 2013, British Columbia passed the Community Contribution Corporation (C3) Act, a first of its kind in Canada, creating a new legal form that would “signal publicly that a company has a legal obligation to conduct business for social purposes and not purely for private gain.” In the B.C. government’s view, this “branding” could help attract capital that is currently not accessible to the social enterprise sector. For the entrepreneur it finally means a legal form that says “We do good and make money”. In 2012, Nova Scotia introduced Community Interest Companies Act which is similar to B.C.’s (C3) but it is not yet in force.

Meanwhile, in Ontario, the capital of business in this country, and 10 years after the U.K. started down this path, we are still arguing about whether or not a hybrid legal form is a good idea.

In February, 2015, the Ministry of Government and Consumer Services released a stakeholder report which summarizes the results of six exploratory discussions with 14 interested parties, mostly non-profit insiders, to gauge support for a hybrid legal form in Ontario. Amazingly, support was not unanimous.

Turns out much of the Ontario not for profit sector, those we entrust having only the purist of motivations to lead society to a better place, are holding back their support at this time; to many, its a curious position for them to take. The Ontario Non-Profit Network (ONN), which represents 14 000 non profits in Ontario issued an “action alert” boldly encouraging its membership to say no to the introduction of dual corporate form legislation. First, they argue that members should not supporting anything new until the new Ontario Not for Profit Incorporations Act, the sector’s governing legislation, is passed into law. In other words, “their” first things first. They would also prefer to see the legislation and tax code change to enable non-profits to increase their allowance to derive revenues from commerical (social) enterprises while still maintaining their tax free status. Finally, the ONN believes that a better use of time and effort would be to improve access to capital to current corporate forms for social initiatives rather than introduce a new form.

The legal profession is also unsupportive and frustratingly agnostic. Most from the legal profession believe that social entrepreneurship can already succeed as it is, and that if one is so motivated, one can simply customize articles to look like a Benefit Corp–for additional fees of $3-5K of course. And if your mission is thrown on the auction block by shareholders or Directors, who suddenly see potential profits where none previously existed, the founder and any supporters can fight them in court to retain a mission first stance—but not without incurring significant legal fees. See the theme here?

What this all means is that at least for now, the most powerful and organized voices affecting the government’s outlook on hybrid corporate legal formation are those who have arguably the least to gain. Defending turf or status quo is the stance. Meanwhile, the growing legions of hybrid oriented entrepreneurs, many of whom are graduates of the new business school curriculum, are too early in their careers to worry about politics, are unorganized and ergo invisible as a constituency –especially to government.

But one has to ask. Why is it that Ontario does not see a need for, or the benefits of, a new corporate form tailored to the needs of for profit social entrepreneurs when B.C., Nova Scotia, and a host of other countries around the globe, including the United States, are in the meantime, racing ahead, assertively designing, and quickly passing legislation to support the emergence of a surprisingly broad range of newly authorized corporate entities in response to not only the needs of their social entrepreneurs, but also their consumers, and global investors looking for clarity when it comes to what defines, and what governs a true social enterprise?

It would be a shame if Ontario, due to failure to really understand the potential of innovating on the corporate form level, was left behind with dust on its face, and global impact investment money going elsewhere as a result.

Enter B Corporations

If Ontario’s social entrepreneurs cannot distinguish themselves from traditional for profit entities via a suitable legal form, what’s a social entrepreneur in this province to do? Some argue there is one more option: Incorporate as a for-profit, then become a B Corp.

Just when you thought this space could not get more confusing, it does. The B Corp is effectively a certification scheme not dissimilar to other certifications, like “Fair Trade” coffee or the “Organic” designation. After first completing a self-reporting survey on a series of environmental, community and employee wellness, governance, and innovation questions, prospective entrepreneurs also need to submit proof of having generated a positive impact in these areas, as well as updated copies of a firm’s bylaws to ensure the organization is firmly stakeholder, rather than shareholder, oriented.

In the U.S., companies are expected to be shareholder-oriented by default in the eyes of the law. Not so in Canada, say most corporate lawyers, however those who have been tested know that shareholders, especially in privately-held companies, still control, and that nice wording in your company bylaws can be easily overturned by a quick vote.

So, while becoming a certified B Corp is one way of distinguishing your enterprise from say, Barrick Gold, the certification is, at least so far, not well known in Canada (143 registered Canadian B Corps out of the over 1.1m enterprises in the country) and, more importantly, has no teeth in the eyes of the law.

It is not a credible substitute for a dual purpose corporate form any more than a car is to a bicycle. True, both will get you around, but a car will get you much further, faster, and more likely, in one piece over a long haul.

So, where are we now?

The last presenter at the Social Innovation Bootcamp is Marjorie Brans. Brans is a feisty, mother of two children under five, ergo no time for bull shit, and also the founder and CEO of the Ontario School for Social Entrepreneurs, housed at the Centre for Social Innovation in downtown Toronto. Her school helps social entrepreneurs develop their ideas, find investors and eventually launch their enterprises.

The attendees, by now a little spent, came alive, nodded in agreement and snapped smart phone pictures of the slide showing the Emerging Technology Hype Cycle, developed by the Gartner Group in 2012. She believes the social innovation/social enterprise idea is following this cycle, starting with a an innovation trigger (in this case, the Wall Street-led financial meltdown in 2008, which triggered global citizen disgust), followed fast by a huge rise of interest and investment (and in Canada, government grants), fuelled by inflated expectations, followed by a period of disillusionment, a slow climb back to enlightenment (the phase where the wheat is finally separated from the chaff) and then finally reaching a plateau of productivity , where proven best practices can now be scaled for maximum impact and returns. Brans argues that the social innovation space has just reached the top of the hype stage and is entering into the trough of disillusionment.

Many agree with her analysis. And if she is right, it looks like the current rush of social entrepreneurs and innovators are in for a hard landing, and that the opportunities—and decently compensated jobs—in the space are still some years away.

Still, none of this deterred those attending the Social Innovation Bootcamp. They came back for each session, heads reeling from more complexity and considerations than any Black Scholes model, and stayed until the very end. They are clearly determined to do well, and do good—in the profit space.

Social innovation space is the new black. It has captured the imagination and attention of even this country’s most traditional business schools. Social innovation and its active ingredient, social enterprise, needs to be a priority for all of us if we are to see our way out of the environmental and social mess that has been created over the past 50 years.

Reports form a variety of government agencies, think tanks, and citizen groups show consistently that income inequality is increasing in Canada, and that child poverty is on the rise. There is increasing pressure on our water quality, and level of individual health and access to healthcare is increasingly a function of income. Food insecurity is a significant issue in cities and rural areas. Many of these issues today are driven by local circumstance and global trends.

Meaningful progress will likely take time. Solving complex social issues is hard enough. The last thing we should be spending time fighting for is status quo in a changing world, or over-thinking existing demarcations between who should/shouldn’t be doing good. It’s time to re-draw the battle lines, consider our competitive stance in the growing global impact space , and re-think how we perceive the role of non-profits and for profits in our future society.

The post Social Enterprise in Ontario: Substance or Style? appeared first on LiisBeth.

]]>