Five years ago, I was a senior marketing executive for a global academic publisher, developing communication strategies for STEM textbooks and public health journals. After the birth of my first child, I requested flexible working hours and was turned down. So, I joined the swelling ranks of mothers in the UK who have turned to self-employment in order to bring in a much-needed second household income while staying at home with my son.

As a publishing media graduate, I had always dreamed of being a writer before being lured onto the more financially stable path of marketing. I saw motherhood as my chance to start again. And so, in-between my son’s playdates, I scoured the internet top to bottom, reading articles like “How to Become a Freelance Writer and Earn $4,000 a Month” and “How to Become a Freelance Writer FAST With No Experience!” in my quest to kick-start a freelance writing career.

I learned enough about the seedy underworld of ‘content farms’ to know that I didn’t want to be the kind of writer churning out search engine–optimized, keyword-rich articles for as little as $2 a piece. While many new writers build a portfolio by writing for free, I would not be one of them.

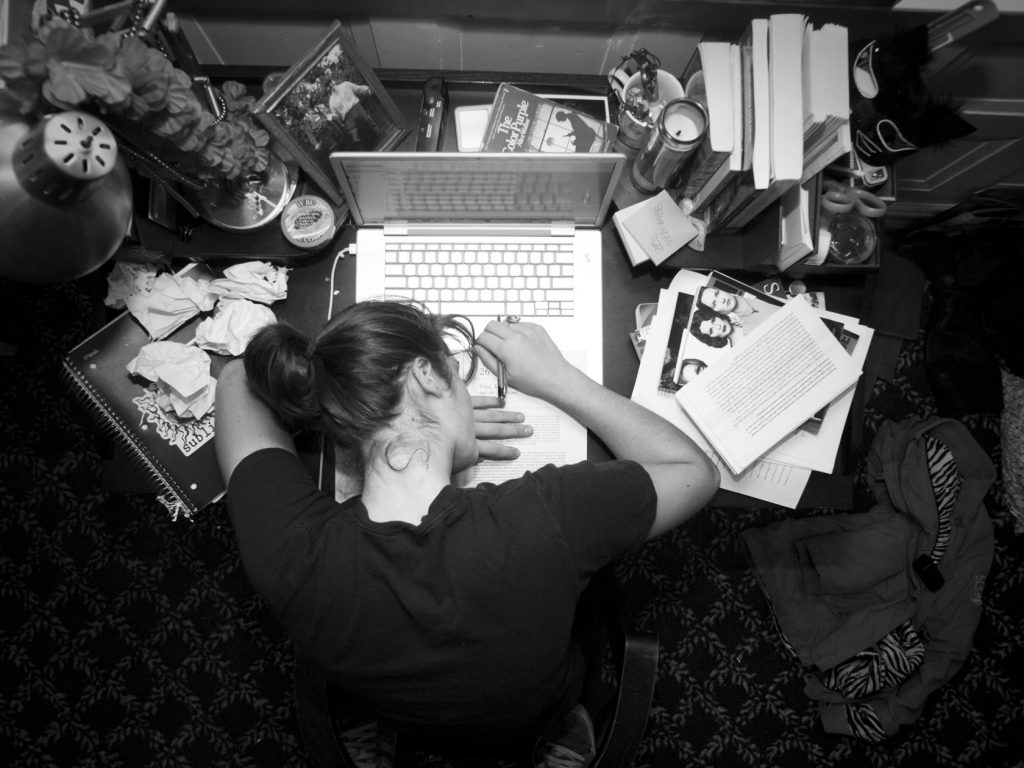

Eventually, I came upon an ad posted by an online publishing platform with a large global readership: “Creative Writers Wanted to Produce Viral Content.” For all of US$17 an article, I wrote about the benefits of lemon water, cold showers, and cuddles. Mother by day, creator of listicles from the absurd to the ridiculous by night. Through the exhaustion of new parenthood, I made up life hacks for success, slimming, and sleep, trying hard to convince myself that I was, at least in some loose sense of the word, a writer. My words, however trivial, were being read on the internet by thousands—and sometimes millions—of people.

Several months in, I spent one memorably fraught evening making GIFS of KonMari folding techniques, before Marie Kondo’s Netflix show was even a thing. After that, I could hack the vapidity of the treadmill no more and set off in search of something slightly higher up the freelance food chain.

I found it in the form of a UK content agency advertising for “experienced writers with a journalistic background.” Though the output was more engaging, I was once again a cog in a machine run by white men. But they liked my writing and were willing to pay £25 a piece (C$48) so it felt like a step (albeit a baby one) in the right financial direction.

When my son was asleep and the washing was on—during what feminist writer Tillie Olsen called the “tag-ends of time”—I wrote about the ramifications of Brexit for American tech companies looking to expand overseas, the power of virtual reality for workforce training providers, and the organic baby food market for a design and branding agency. Though the deadline/family time balance was ever precarious, I genuinely enjoyed both the research and the writing (tea, silence, blurt:edit:polish).

And then I accidentally discovered the vast chasm between what the content agency was charging their clients for content and what they were paying me to write it. It was like 15 times more. I had not thought myself naïve, but the discovery shocked me out of my breastfeed-write-sleep-repeat routine long enough to realize that, somewhere between my eagerness to write and my willingness to please, I had been financially exploited.

From planning to publication, each article took me an average of five hours to complete. No matter how I looked at it, I was working for well below minimum wage. But for the self-employed, entrepreneurs, and freelancers, there is no mandated minimum wage. Some writers charge per day while others by project, word, or hour. New as I was to the game, setting my fees felt like a guessing game, with my sense of self-worth at one end and how much the client is prepared to pay at the other. And, since that client might be a cash-strapped startup or a corporate giant, there was a large sliding scale between the two. Meanwhile, I was competing against an almost endless supply of budding writers caught in a race-to-the-bottom wage war.

But I began the process of determining my worth by working out my ideal effort-to-earnings ratio. I requested a third more money per article. The agency agreed. Suspiciously quickly. In pitching myself too low, I had fallen foul of the “motherhood penalty,” as reported by 40 percent of US creative freelancers, the price to pay for familial flexibility. But after another six months, I went after a more ambitious uplift of 50 percent and won it. Two years on, I finally feel that, at £250 (C$430) per article, I am being paid a fair price for my work.

And then I began to realize that my dissatisfaction with content writing was never just about the money. Seeking fair pay provoked a wider awakening, prompting me to question some of the deeper inequalities within the content writing industry.

As a content writer, I create blog posts and thought leadership articles for business leaders, startup founders, and creative agencies. I do the research, thinking, and writing, but they get the credit for authorship with that coveted byline. This is simply how the global content marketing industry works. And it’s seriously big business (projected to be worth US$412 billion by 2021), with a 16 percent annual growth rate.

Then one day, an article I wrote for an app developer was featured in an industry publication. I had written plenty just like it but this time, the thrill of seeing my words on screen was tempered by the irritation of seeing the managing director take public credit for them.

I tried to develop a transactional mindset, but consciously commodifying your work is easier said than done. While readers implicitly understand that certain types of text (web copy, white papers, press releases, marketing material) are curated either collectively in-house or by an outside agency— with the copywriters accepting total anonymity as part and parcel of the job—content writing is often a much more personal affair. Even the most clinical of content writers trail nuanced wisps of themselves in syntax, style, and substance.

But we don’t get a wisp of credit. Over time, as I wrote opinion-driven, long-form articles for mostly male business leaders, my exchange of service for money had become a more problematic entanglement of submission/power. When I became the sole writer behind a series of first-person articles credited to a male entrepreneur, I started to really question the feminist implications of my work.

The articles were for an online platform celebrating and encouraging ethical business practices. Writing on behalf of that male entrepreneur, I extolled the virtues of trust and transparency in leadership, called for an end to unpaid internships, and promoted planet and people-centred policies. I was writing about everything I believed in. Therein lay the problem.

Because in writing “under his name,” my own identity diminished. I’m certainly not the first faceless female freelancer to write opinion-led articles that are publicly credited to someone else. I’m probably not the first to feel ethically uneasy about it either.

Of course, there are male content writers—just as there are female CEOs who engage them—but, as a female ‘thought provider’ to a male ‘thought leader,’ I was beginning to draw connections across the wider business world in which women do the hard thinking and men take the credit.

What, then, was the answer? Leave content writing for journalism and get proper public recognition for my work? That may resolve my feelings of discontent, but I also had to confront the uncomfortable truth that, since He has the authority and business reputation, I was more likely to be ‘heard’ writing under His byline. Thanks to the media’s devaluation of the female experience, my own story ideas were unlikely to command the column inches nor the publication rates of those within the Straight White Male paradigm. Do I remain an invisible but reasonably well-paid content writer? Or a financially struggling but satisfied freelance journalist?

For a while, I tried to enact change from within, using my anonymity to redress the gender imbalance as I saw it. I proposed features that celebrated International Women’s Day and made the business case for diversity. I prioritized quotes from female business leaders over male ones and wrote about businesses that had a poor track record on inequality. All the while signing off as Him with a personal flourish. On the surface, my subtle acts of resistance seemed positive, but I also worried about unwittingly leading readers to think that gender bias in business is less of a problem than it really is.

Writing as Him, I advocated for total supply chain transparency in manufacturing. As myself, I am calling for the same premise to be applied to the content writing industry. Specifically, I would like to see businesses publicly acknowledge the co-creational contributions of freelance writers, just as they would credit the designer who built their website. If work must be ghost-written on first publication, I recommend at least letting writers claim credit on their website. If not, writers should be able to charge a premium.

For me, content writing has served its purpose, allowing me to develop my craft and build a portfolio. But it has also become an affront to my own potential, denying me both authorship and agency. Beginning in 2019, I am reclaiming both, writing under my own name and using my words to voice a new narrative—my own. My new web portfolio features a new section entitled ‘This Is Me.’

Financial Tools of the Trade

Check out these national writing associations for recommended pay rates: London Freelance Fee Guide, the Editorial Freelance Association in the US, and the Professional Writers Association of Canada.