We all heard the news. Once again, Catalyst Canada, whose mission is supposedly to accelerate progress for women through workplace inclusion, has named a man as chair of its advisory board.

People across the gender spectrum, in both mainstream and social media, were quick to respond to the irony of the appointment of CIBC’s 51-year-old CEO, Victor Dodig. The most common reaction: WTF?

Catalyst’s executive director Tanya van Biesen was equally quick to defend the choice to the media and on stage. “We need to include men in the conversation,” she repeated. “Especially powerful visionary men,” she added, as though Dodig’s appointment were part of a new and bold strategy for the organization—and for the advancement of women.

The thing is, it’s more like an old, tired strategy. Most media outlets have reported that this was the second time a male bank CEO has been in the board chair. In fact, it’s actually the third time in a row. And substantial evidence shows it just isn’t working.

Catalyst Canada is a branch of the Fortune 500 non-profit consulting practice and research organization based in the US, which has a pay-to-play membership. Since its inception in 1962, the US parent has always had a man as its board chair. Ditto for Catalyst Canada.

Furthermore, in the last 10 years of Catalyst Canada’s existence, it has had the distinction of having the lowest number of women on its board—just 36%. The US has 42%. Most other regions hover around 50%, although Catalyst Europe somehow found a way to give women a majority voice on its boards with 76% representation.

So what can we learn by going beyond the obvious optics issue, and taking a closer look? At what point does a catalyst become an inhibitor of the advancement of women by providing a convenient cover for major corporations whose “activism” amounts to little more than paying for the right to mention their Catalyst membership in their annual report to appease employees and regulators?

Has depending on male CEOs helped advance women?

If Catalyst Canada were rated on performance against stated purpose, like any division in a FP500 corporation, it would probably have been sold off by now. If it were a startup, it would have been told by investors to pivot or lose support.

Here are the statistics to show how far behind we still are:

- In Canada, women comprise only 14.5% of the Financial Post (FP500) director’s list. Take out crown corporations and the number drops to 10%. More than 40% of FP500 companies have no women on their boards.

- Of the 677 companies listed on the TSX, women held 12% of all board seats, up from 11% the year before. But in that year, 521 board seats became available and only 76 women were appointed.

- Catalyst’s own 2017 report on women in Standard & Poor’s 500 Index of the largest global corporations shows only 24 had female CEOs—or just 5%.

- The TSX introduced a “comply or explain” diversity policy to encourage companies to appoint more women to its boards. It managed a meagre increase of 2% between 2015 and 2016.

Not only is performance lagging, so is aspiration. In 2012, Catalyst Canada set a target for its 100-plus Canadian corporate members to have women comprise 25% of its board members by 2017. In the five years since, it has not increased this target-despite being a “powerful” male-dominated board.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau set a goal of appointing 50% women as cabinet ministers to lead the country—and did it. A good number have even proven to be among his most effective performers. Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne implemented a 40% quota as a bare minimum for provincial boards and agencies to achieve by 2019 out of frustration at the glacial advancement of women into the boardroom.

What does it say when government outpaces the speed of business? And why don’t we act on research that shows that changing systems and implementing quotas work a whole lot faster than relying on changing mindsets?

Witness the perils of groupthink

Groupthink is “when a group or organization begins to make decisions that neglect to rely on ‘mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment.’ Groupthink happens insidiously, over time, and is most likely to occur when individuals in a group share the same background, language, values, and fears.”

Sallie Krawcheck, founder of Ellevest and former president of the Global Wealth & Investment Management division of the Bank of America Group, says groupthink was the real cause of the 2008 financial crash. “As someone who had a front row seat,” she explains, “there were no evil geniuses pulling the strings.” Just guys who all look and think alike, and as a result, “didn’t see it coming.”

Groupthink is serious business. And Catalyst knows this-at least intellectually.

Catalyst’s research says that to reap the bottom-line benefits of diversity and inclusion practices, you have to aim for true diversity of thought, not just ensure that you have a balanced set of genitals around the leadership table (okay, that last description was ours).

No matter how you slice it, it’s difficult to see how Catalyst Canada will muster diversity in its thinking with this latest move. Especially when the board is so homogeneous to begin with. Eleven of its 18 board members are not only men, but white men of, shall we say, a certain age (50 plus). The women on this board are no shrinking violets but they are also long-time members of the same elite corporate community. The intertwined financial and professional services sectors they represent are disproportionately represented. So it’s no surprise the board voted the CEO of one of Canada’s largest banks to lead Catalyst. Dodig is a competent, safe, “looks and sounds just like me” choice. He’s an insider, which makes this decision a shining example of groupthink. It’s also the kind of corporate cronyism that Catalyst’s own reports cite as a key factor in keeping women out of leadership jobs.

What’s that strange sucking sound?

No doubt, Catalyst’s research is valuable. It tells us how well—or not—corporate Canada is advancing women in the workplace. It also tells us how little has changed despite Catalyst’s advocacy in advancing equality in the workplace. With this recent status quo decision, it’s fair to ask if its credibility is increasingly at stake.

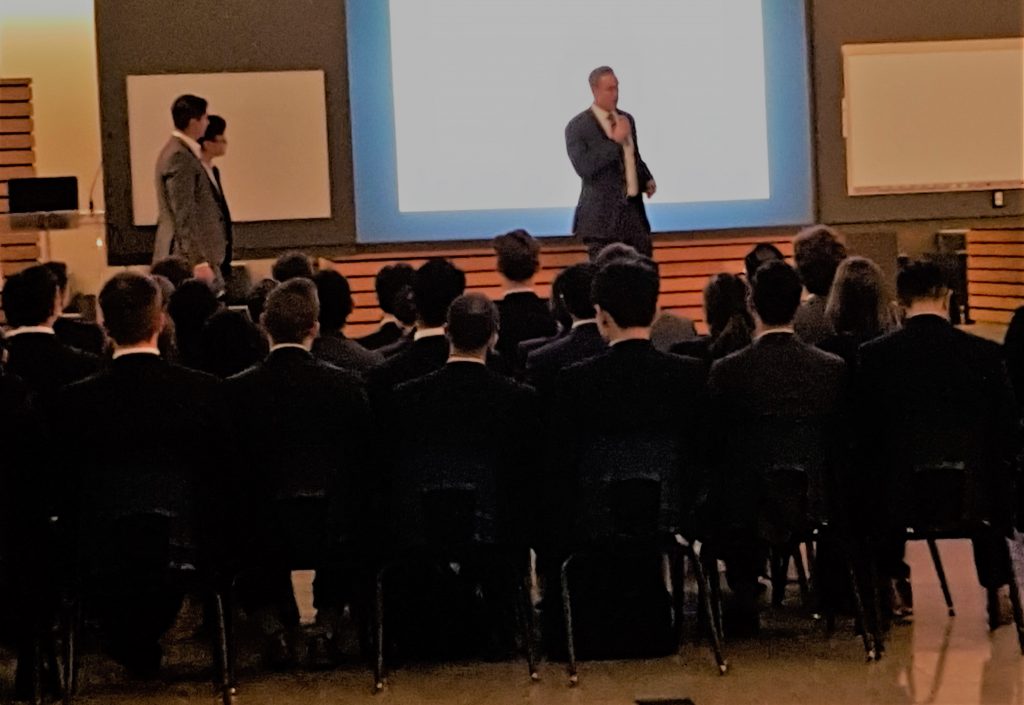

Three weeks after Dodig’s appointment, Catalyst’s executive director tried to defend it again at an October 3rd Rotman School of Management talk on gender inequality. Van Biesen, who spent 11 years as an elite corporate headhunter before joining Catalyst, could have used her talent to identify, attract, and promote a fresh alternative as chair. The board could have been imaginative and elevated someone who would have generated applause versus a dark cloud of side-eyes. But instead of reaping support, van Biesen is now mired in arguing, essentially, that to advance women we must give powerful white male business leaders the pedestal to do so. History, the data, time and time again, has proven otherwise. Try to name a single white male corporate CEO who has challenged systemic racism, sexism, classism, and other forms of marginalization to realize game-changing outcomes?

This work is always done most effectively by people who think differently, and often people outside the system, not those who benefit from being in it. Just ask the suffragettes. Or the Indigenous grassroots leaders of the Dakota Access Pipeline protest.

Michael Kaufman, a feminist and co-founder of the White Ribbon campaign to end violence against women, says that men who hold majority power can still be useful allies in the fight for gender equality, but only if they are honest about recognizing that there is something they must give up. “It’s called the patriarchy,” he says.

As Gloria Steinem says, “No one can give us [women] power. If we are not part of the process of taking it, we won’t be strong enough to use it.”

Catalyst missed an opportunity to pull a Wonder Woman move.

New times call for new measures

In 2017, we saw the largest women’s rights march in history in Washington and Canada. It was a revival of the feminist movement in response to hard-won rights rollbacks, major takedowns of sexist CEOs (Uber, 500 Startups), rising inequality, populism, major lawsuits regarding tech sector misogyny, and women finally re-gaining permission to drive in Saudi Arabia. These are turbulent times.

Dodig is a lovely man (I have met him myself) and he’s a convenient, practical choice for chair, but not a spirited one in times that cry out for fearless actions. If Dodig really wanted to demonstrate both the understanding of the power of allyship and his dedication to advancing women in the workplace, he could have declined the nomination and helped van Biesen recruit a woman who doesn’t look or think like the status quo. That would have shown real commitment to the cause—and selfless leadership. He has already served for three years as director of the Catalyst Canada Advisory Board. He could have continued to serve and carry on while being a positive force for change.

Catalyst, or rather its members, have great influence in our economy, but when it comes to wielding their collective power, they again reached for a butter knife rather than a metaphorical sword.

Related Articles

Women’s Empowerment Group Catalyst Canada Says It Believes In Strength Of Male Leaders (Huffington Post), Sept. 15, 2017