You are visiting Liisbeth’s archives!

Peruse this site for a history of profiles and insightful analysis on feminist entrepreneurship.

And, be sure to sign up for rabble.ca’s newsletter where Liisbeth shares the latest news in feminist spaces.

A couple years back, I sat in a room full of women executives in pantyhose as keynote speaker Dr. Sherry Cooper (former Chief Economist and Executive Vice-President of BMO Financial Group) profoundly shifted my perceptions about women’s self-employment.

Like many who throw around words like “incubator” and “accelerator,” I viewed the narrative around growing numbers of female entrepreneurs as a sign of progress.

That day, Dr. Cooper’s Powerpoint featured a chart that showed that while the number of female entrepreneurs is on the rise, the income of women entrepreneurs is pitifully low compared to the average income for Canadians.

Having been an entrepreneur myself, I know that the romantic ideal of entrepreneurship does not always align the reality. Think about the majority of female small business owners you see in your daily life. The wife of the couple that runs the convenience store on the corner. The lovely woman who runs that little flower shop. Chances are she’s just scraping by. You read it on her face.

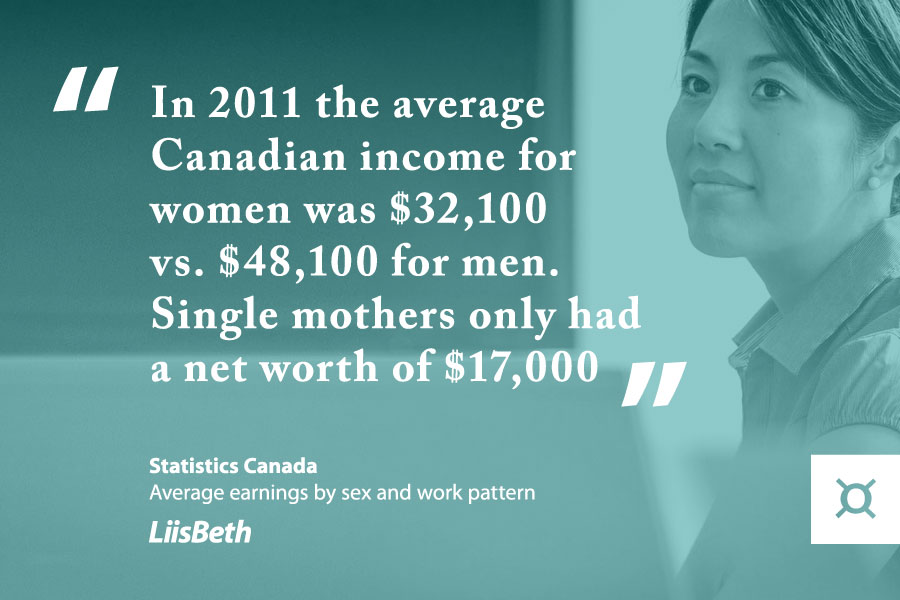

In Canada in 2011, the average income for women was $32,100 (compared to an average of $48,100 for men). Single moms in this country have a net worth of about 17,000.

Dr. Cooper’s chart made me wonder if promoting entrepreneurship is really a useful strategy to help lift women out of poverty?

The Canadian Women’s Foundation invested $4.5 million in economic development programs from 2009 to 2014 to help women begin moving out of poverty. One stream this of funding is dedicated to women’s entrepreneurship. Chanel Grenaway, The Foundation’s Director of Economic Development, helped shed some light on the question of whether entrepreneurship is a sound strategy that addresses the needs of women living in poverty.

The short answer (spoiler alert) is that women on low-incomes do indeed benefit from self-employment programs. However, the impact of these programs are are profoundly influenced by the real limitations women living in poverty face.

Limitations to Self-Employment Programs for Poor Women

Access to Capital:

Women living on low-incomes have a hard time securing loans. Lack of solid credit history or risk-aversion makes it harder to launch a business idea. Even if they could access funds, women who are at risk of homelessness or hunger see dipping deeper into debt a as something to avoid at all costs. Consider the fact that 82% of the women who participated in The Canadian Women’s Foundation’s self-employment programs name ‘housing’ as a core need.

Business Vision:

It is a common dictum that the key to success is to “do what you know.” Yet, in the case of women, a great cookie recipe, a knack for jewelry making or childcare experience is not likely a recipe for economic sustainability. How do we encourage women to move beyond what they know to develop scalable business ideas in high growth areas?

Time:

Women living on low-incomes are beyond over-extended. It’s hard to dedicate time to building a business if you can’t afford childcare. The truth is, most women in these circumstances are “job-patching” which means they’re working multiple part time jobs to make ends meet. This precarious-work model has a disproportionate impact on women, who largely oversee childcare responsibilities. In this context, creating a business becomes an “off the side of the desk” project which just doesn’t make the grade when launching a new business.

So, what can help make self-employment a viable pathway for women to move out of poverty? Here are some preliminary ideas Chanel Grenaway shared with me based on her tenure at the Canadian Women’s Foundation.

Tools to Dream Bigger:

Women need tools to help them develop businesses ideas beyond the familiar. Grenaway puts it best when she says “we need to help women dream bigger.” This strategy requires what she calls, “thinking beyond jams, jellies and sewing.”

Grenaway says that the process of growing female entrepreneurs needs to start early. Girls, she says, need tools to see themselves in new ways. For Grenaway believes this means that girls and young women need mentorship, job shadowing and education programs that can eliminate the gaps in their own thinking.

Policy Levers:

Grenaway insists that there’s a need to reform policies that profoundly impact woman’s capacity to move out of poverty. Lack of access to affordable daycare makes it nearly impossible for women to navigate their way out of subsistence living. Also, precarious “just in time” work schedules have an enormous impact on low-income women. Women need predictable, stable incomes to plan to return to school or start a small business.

Benefits Beyond Business:

Ultimately, Grenaway believes that programs like those funded by The Foundation help grow women’s personal assets. Women don’t always become successful business owners as a result of participating in the programs funded by The Foundation. The evidence does show, however, that these programs help women living in poverty build the confidence they need to pursue more education, start another business or enter employment. These skills are often called “soft” skills, but there’s nothing soft about them. As Grenaway puts it: “If we aren’t going to build these kinds of skills for these women, then who will?”

You are visiting Liisbeth’s archives!

Peruse this site for a history of profiles and insightful analysis on feminist entrepreneurship.

And, be sure to sign up for rabble.ca’s newsletter where Liisbeth shares the latest news in feminist spaces.