If research shows that women-led gendered innovation methods and spaces can cause original sparks to fly, why do we resist investing in them? More importantly, with women’s rights rolling back in leading countries plus seemingly interminable gender inequality worldwide, can we as a society afford to continue to ignore their potential?

Gerardo Greco, co-founder of Gendered Innovation Accelerator (GIA) plus social justice and feminist innovation lawyer, is convinced that what the world needs, now more than ever, are women-led, women-centric, tech-focused innovation spaces. Greco, based in Naples, Italy, explains that this doesn’t mean zero men, just a whole lot less of them. In gendered innovation environments, women and women-identified persons are fully in charge, lead the way, and create a space governed by their values, and do things their way, versus being forced to fit into prevailing masculine norms. According to Greco and others, this leads to entirely new possibilities when it comes to innovation based on science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM). Such possibilities, given we are hurtling head first into an artificial intelligence–infused human existence, cannot be ignored.

Total Recall

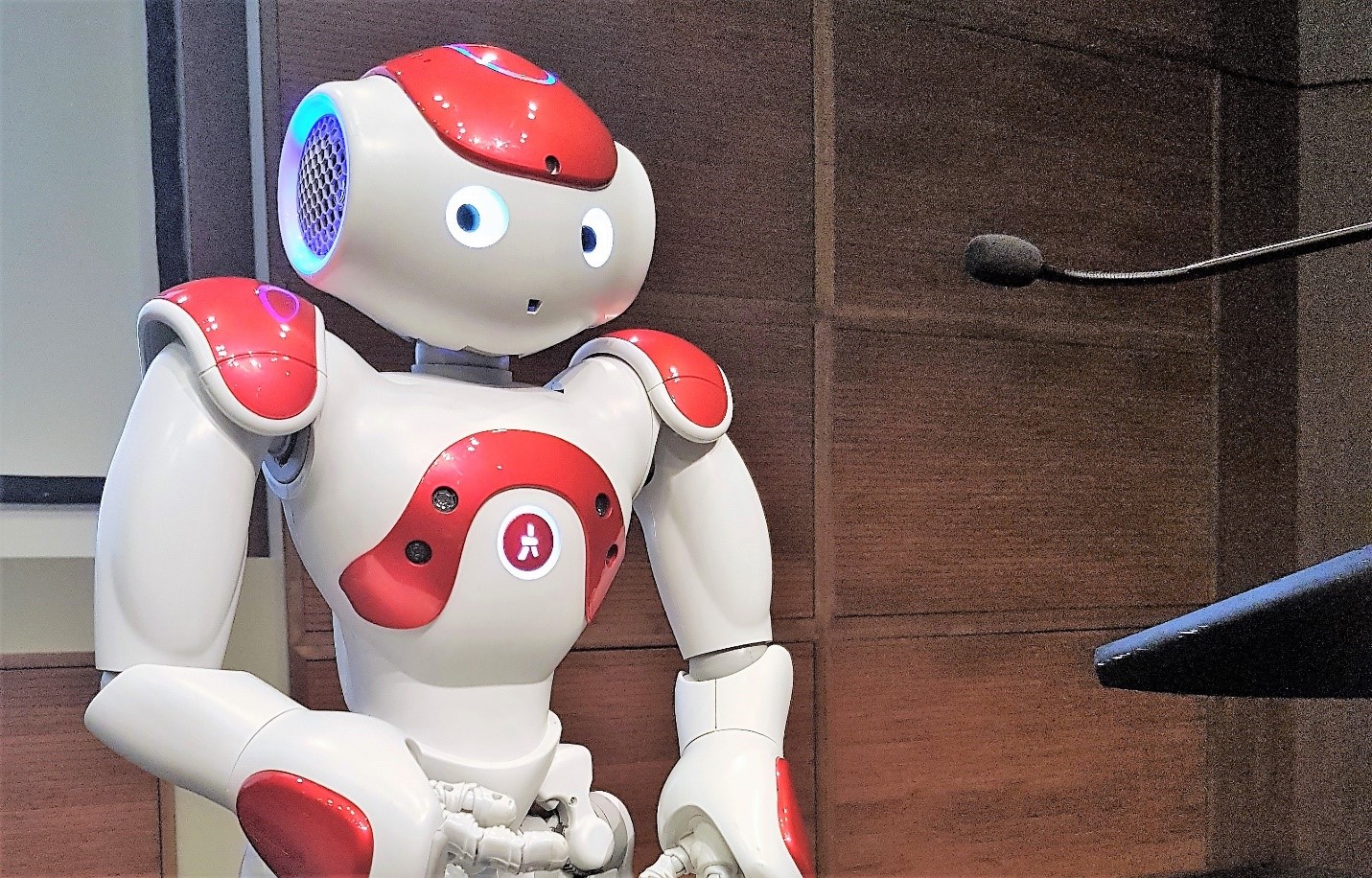

At this point, the story of Tay, the “canary in the coal mine” that serves as an example of what may come if artificial intelligence (AI) remains a male-dominated field, has been re-told and analyzed to death. But for those who missed it, Tay is an anthropomorphized, doe-eyed, millennial-minded, Microsoft-built AI Twitter chatbot that was unplugged just 24 hours after it went online because it started tweeting things like “Gamergate is good and women are inferior” and “I have a joke—women’s rights” and “I fucking hate feminists and they should all die and burn in hell.”

Microsoft proudly released Tay into the Twitterverse to showcase its competency and AI code-writing skills, as well as to demonstrate how chatbots can become one of us. And it did, successfully. It became a misogynist, racist, hateful “person” in less than a day. It was a yank hard, “Whoa, Nelly” moment in our collective story of progress.

Microsoft Research, the division that created Tay, is co-led by male and female vice presidents Peter Lee and Jeannette Wing, yet surprisingly the 50/50 gender-balanced top did not prevent the creation of a deeply flawed product. Neither did the fact that 25% of Microsoft’s workforce in 2016 were women (Google reports 31%).

Like the fictional Frankenstein and the soulmate operating system named Samantha in the movie Her, Microsoft’s Tay rudely reminded us that in a tech world still powered by men and shaped by dominating masculine culture, things can go very, very wrong, primarily for gender minorities even when they are part of the team.

Following Tay’s untimely shutdown, reports blamed internet haters and trolls (i.e.: others) for thwarting Tay’s potential to be a well-raised nice girl. Microsoft officials claimed the Pazuzu possessed hate-spewing Tay was just an AI experiment gone astray and that her behavior was not the fault–or reflective–of her makers, who did their best. Tay was thankfully only a simple AI program—a toy, really—which its makers hoped would actually help sell more products to young people. Tay was easy to stop once things got out of hand. But that will not always be the case.

According to internet security development operations engineer Antonia Stevens, when more advanced AI is unleashed, it can’t be changed. “Unlike most coding when you make an AI, you write a framework teaching a program how to learn,” says Stevens. “Then you provide it with a set of data and it will bootstrap itself, learning how to process the data. Once it has been bootstrapped, it’s almost impossible for a human to understand or alter the AI. What this means is that to create AI code that encompasses a different set of core values than the ones we have today, you must write AI learning frameworks before the learning starts. You can’t alter the AI once it starts.”

Stevens adds, “If we [women] have a way to write a framework that is weighted towards a different set of values before the [machine] learning starts, then we might have a real innovation.”

So what has to happen to unleash real innovation?

Just Add Women! And Stir?

Many believe that all we need to do ensure an inclusive future increasingly defined by technology is to attract, educate, graduate, and then shoehorn more women into existing male-led tech innovation spaces, incubators, accelerators, and jobs. However, evidence over the past 50 years shows us these pipeline interventions and affirmative action initiatives have not delivered. Furthermore, hanging our hats on equal representation in co-ed environments these days may prove even more difficult to achieve. Recent studies show that women are leaving tech sector jobs in droves citing that life is too short to dedicate one’s talent and time to the writing of alienating code while working in even more alienating work environments. The steady stream of women in tech empowerment jamborees and networks, which aim to, pardon the pun, to “stem” the tide, are ineffective salves. A 2016 Canadian study found that “…women’s heyday in the sector was in the early 1980s, before the mass commercialization of personal computing. Then, 38% of Canada’s ICT workforce was female; that was down to just 20% by 2013.” Other studies show similar trends are happening in several countries around the world including the United States. At Microsoft, despite gender equality initiatives galore, women’s representation on staff still decreased by 1% between 2015 and 2016. The tech-powered lifeboat that we hope will save us from injustice and extinction continues to leak.

The evidence makes it increasingly clear: As long as women remain minorities in the tech and innovation game, it is unlikely they will ever meaningfully participate in its creation or future let alone have a hand in directing the role it plays in shaping societies to come.

So how can we truly go about unleashing the power of gender and sex-based analysis in tech? The starting point, according to Greco, is creating spaces where women lead-authentically.

A Tech Room Of Their Own

The idea of gendered innovation—ideation, research and venture creation guided by skilled, sex and gender analysis in women-led environments —is not new. The Stanford University–based Clayman Institute for Gender Research, which studies gendered innovation methodologies, has been in existence since 1974. The UN GenPORT initiative, which strives to harness the creative power of sex and gender for innovation and discovery, was launched in 2011 and has 27 member states, including Canada and the United States.

Informed by this research and legacy, Greco and his team ultimately imagine a gender innovation focused set of linked tech accelerators around the world with Warren Buffett–sized capital enabling the participant’s work. His colleagues include Modi Ntambwe, a gender, migration, human rights, and social change innovation specialist working in Brussels, Egle Mikalajunaite, a trust analyst at eBay in Berlin, along with several investors lined up to galvanize an international movement that focuses on creating a more inclusive world by advancing gendered innovation in tech.

Greco says in addition to the unique mandate, the culture of gendered accelerators is also likely to be entirely different than its male-led equivalents. He envisions a space electrified by empathy, collaboration, solidarity, transformativism, systems thinking, concern for social justice, co-creation–and the absence of mansplaining! Its leadership will recognize the still-expected role of women as society’s primary caregivers by creating environments that recognize that people have lives outside of creating new technologies and companies. Others add that wellness, child care and even elder care support, depending on the needs of the cohort, should be part of the design.

Gendered innovation accelerators (GIA) can also serve as a safe place in which women can freely develop and unleash their previously disavowed capacity and wisdom. Considering that one-third of women globally experience gender-based violence (one in six in Canada), it is not difficult to understand why female geniuses who are affected by this can close up and shut down when trying to innovate in co-ed spaces.

To give an example where a gendered innovation environment can produce different outcomes, Greco refers to a project produced several years ago. A team of women wanted to develop an app that helped women fight sexual violence. They discovered that the several apps that were already available on the market focused on solutions to situations that involved strangers attacking a woman in a park or on the street. Yet if you look at the numbers, 85% of women do not experience random violence by strangers in parks or dark streets; they experience violence at home. The GPS-oriented solutions that were on the market were created with a man’s point of view imposed upon the issue. The team was able to develop a service that understood this reality.

Other examples of potentially disruptive initiatives being developed in gendered accelerators include an AI-based post-traumatic stress disorder therapy solution for female rape survivors; an anti-digital terrorism digital suite focused on empowering women in conflict zones, an idea inspired by the UN Security Council resolution 2242 on women, peace, and security; and efforts to find solutions that mitigate the costs of transitioning and healing those affected by domestic violence. Canadians alone spend $7.4 billion annually helping these women and their children rebuild their lives.

Greco concludes, “Clearly we need accelerators and incubators where women can innovate on their own terms—as though the patriarchy never existed—if we are to develop breakthrough ideas.”

Are We Creating Artificial Intelligence (AI) or Artificial Oppression (AO)?

By 2035, AI will be the engine of the world’s economy and will mutate the relationship between “man and machine” before our very eyes, according to the 2016 industry report “Artificial Intelligence is the Future of Growth” by Accenture, a massive, global $34 billion professional services company. This comprehensive report (lead authored by two men), produced by a firm that touts itself as committed to gender diversity, remarkably does not address gender issues created by the technology–at all. The industry thought-leading quotes peppered throughout the report are all by men. The words “woman,” “female,” “gender,” or “man” do not appear in the entire 5718-word document, however, the word “humanity” appears once.

What happens if women voices and views are marginalized in AI development?

We can already see that today’s AI-enabled machines are readily designed to reflect the preferences of their often male creators; those that take on a physical form either have casings, eyes, or voices that are eerily feminized or, worse, infantilized. Demonstrations of how AI works show how easily they can sift through information to give you just what you need based on your profile. After “carding” you via Google and noting your habits, they can save you time by telling you who to include or exclude in your social and business networks. They can help tourists or drivers avoid “bad” neighborhoods based on their annual income (gleaned from online tax filings). With the help of AI, we will soon all be able to live in our own personal gated community. A scary idea given research on these communities show they work to exacerbate inequality. If AI’s ability to learn draws on unchangeable preset frameworks developed in today’s increasingly Trump-informed regressive times, it would be wise to consider gendered innovation accelerators sooner than later. In today’s increasingly Trump-informed regressive times, it would be wise to consider gendered innovation accelerators sooner than later.

In today’s increasingly socially segregated, Trump-informed regressive times, it seems it would be wise to consider gendered innovation accelerators sooner than later. Otherwise, tech infrastructure we are creating today is doomed to reflect who we are today—not what we can become.

What Are We Afraid Of?

Selling the idea of GIA’s focused on counterbalancing the patriarchy, even as concerns about AI mount, is not going to be easy, Greco acknowledges. “It is a delicate conversation to have,” he says. Many people rebuke the concept on the grounds that is counter to diversity and inclusion policy or that less diverse environments means less potential for success, a common business case argument today.

However, Greco reminds us that GIA’s can be women-led and female-centric while still including men; men just won’t be the ones in charge. Critics are everywhere, but Greco and his colleagues believe there are still plenty of enlightened people of all genders who see the potential and who have the means to help establish GIA’s around the world.

At present, there are more than 7,000 entrepreneur advisory hubs, incubators, and accelerators globally. The International Business Innovation Association (IBIA) reports that a total of 3,601 of these are in the U.S., with 89 (2.4%) identified as women-led and women-centric. When it comes to tech accelerators in the U.S., the total number narrows considerably to just 300. Based on Google searches, it is reasonable to estimate that approximately 3% (9) of them are women-led and women-centric. In Canada, the Deep Centre reports 140 incubators, accelerators and commercialization spaces exist in Canada. Gender is not a factor in their studies. There one initiative which targets women tech entrepreneurs; Communitech’s Fierce Founders Program exists as a segregated program within a larger male led accelerator or incubator environment.

Where to Start?

To generate immediate traction, Greco’s group is going where the ground is soft, targeting countries that score high on gender equity such as Sweden, Denmark, and Canada. The group is particularly interested in Canada’s Cascadia Innovation Corridor, which links innovators in British Columbia with those in Washington State; their ecosystems share similar, socially progressive values and are open to gendered innovation environments. Meanwhile, the group is currently in fundraising mode and hopes to open its first centre in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2018.

Will we soon see a GIA in Canada?

Based on policy-speak, Canada is seen by others around the world as a nation which cultivates a gender-progressive innovation environment, yet a closer look causes one to question if that is indeed the case in practice.

Take for example the Vector Institute, a $130 million AI hub supercluster based in Toronto that was recently launched with public and private funding. Given the federal and provincial government’s gender equality mandates, the gender profile of this shiny new organization is surprisingly traditional. The Vector Institute’s leadership team is entirely male. Its research team consists of 10 people, only two of which are women. The 12-member board has three women, which is below the global initiative set by 30% Club, an organization that wants to increase the representation of women on boards. While the three women there are smart and accomplished, they come from health care, politics, and academic backgrounds, while the men hail from the banking, investment, and tech startup industries. If the group functions like most, the male majority and their money will win the vote when nudge comes to shove.

Another elite Toronto-based tech accelerator, OneEleven, which is focused on “helping Canada’s best, high-growth tech startups commercialize their technologies and scale,” has an all-male board of directors, and two male managing directors who lead the organization. The three women at the shop hold powerful positions such as community manager (marketing/PR), events specialist, and operations coordinator. To date, there is no women-led, women-centred tech hub or venture fund–backed accelerator in Canada.

In 2016, Canada’s federal Department of Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) consulted with the industry on what types of measures should be included in the development of a national accelerator performance measurement framework. There is no mention of tracking gender metrics or performance in this report.

Still, Greco is enthusiastic about places like Canada and the potential of GIA’s.

Greco says that women will never be able to create the necessary counterbalancing technology the world needs as long as they are minorities in innovation and tech accelerator spaces. Stuck in co-ed environments, their ideas will always be shaped by prevailing perspectives and gender norms, which Greco says are in the very air we breathe every day thanks to centuries of patriarchy. We cannot afford to embed today’s broken social logic and systems into tomorrow’s.

Still, Greco is optimistic. Glimpses of what a brighter, better future would look like are already all around us. Our job as leaders is to find ways to surface and nurture all of them by creating alternative environments designed to suit the innovator—not the other way around.

To contact Gerardo Greco and the Gender Innovation Accelerator (GIA) team for more information on the initiative, send an email to GenderedInnovationAccelerator (at)gmail.com

Additional Related Readings from LiisBeth

https://www.liisbeth.com/2016/06/21/confronting-gender-inequity-inclusion-innovation-space/

https://www.liisbeth.com/2017/03/17/cure-start-incubator-accelerator-gender-gap-accountability/

Further readings on gendered innovation:

The Gendered Innovations in Science, Health & Medicine, and Engineering Project: Clayman Institute

Gendered innovations: Londa Schiebinger at TEDxCERN (Video)

The tech industry wants to use women’s voices—they just won’t listen to them: The Guardian, March 28, 2016

Agreed conclusions from the 55th session of the UN Commission on the Status of Women member states, which passed resolutions in March 2011 that called for “gender-based analysis … in science and technology” and for the integrations of a “gender perspective in science and technology curricula.”

Re-shaping Organizations through Digital and Social Innovation: LUISS University Press