Last month, I set out to find examples of advanced feminist enterprises that were doing truly radical work, showing us what a socially just, post-capitalist enterprise and economy might look like.

FoodShare, a large and innovative Toronto-based food justice charity, emerged as a provocative example.

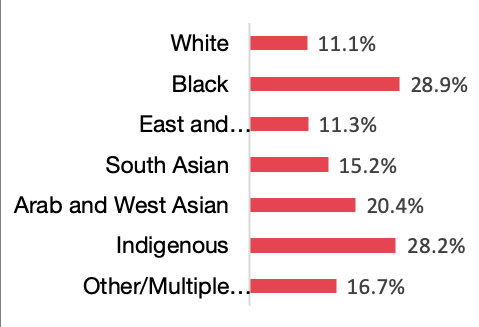

FoodShare was founded in the 1980s in response to an alarming increase in hunger and food insecurity due to the recession, with Indigenous and Black households experiencing the highest rates of food insecurity. It was meant to be a temporary organization dealing with a short-term issue, but as the number of food bank dependent and food insecure people in Toronto grew, so did FoodShare. Today, it is the largest food security charity in North America, entering another rapid growth period due to the pandemic.

FoodShare has more than a dozen income-generating and grant-supported programs including community garden facilitation, kitchen incubator, school lunch programs and a good food box delivered to subscriber doors. The organization employs 120 people of whom 54.8 per cent are women, 1.6 per cent transgender and 2.3 per cent gender nonconforming. While most Canadian organizations are just beginning to embrace the government supported 50-30 challenge (which calls for corporations to increase representation of women to 50 per cent and BIPOC representation to 30 per cent on boards), FoodShare’s board of directors is already 62 per cent female and 85 per cent BIPOC.

Debbie Fields founded and led FoodShare for more than 25 years. Paul Taylor, took over as Executive Director (ED) in 2017.

Here’s what he has to say about FoodShare’s latest progressive initiatives.

LiisBeth: Do you identify as a feminist?

Paul: Of course! I was raised by a bad-ass Black woman and come from a long line of bad-ass community minded, Black women. I was taught to listen and learn from women, and in particular Black women in leadership. I saw, through my mother’s eyes and experiences, how the patriarchy drives the kind of capitalism and neo-liberalism that’s wreaking havoc across the country. The pandemic has further exposed how much we still undervalue women in society. I think it’s horrific that we are just now starting implement a national childcare policy. If this was something that men depended on, we would have had a national childcare program decades ago.

LiisBeth: What do you think is the most radical change you have initiated since you joined the organization in 2017?

Paul: I would have to say our focus on implementing a standard-of-living wages, equal wages and wage-range compression policy.

Over the last few years, we have increased the lowest paid colleague salaries by 25 per cent. And we are not stopping there: we’ve got another increase that we’re working on that will be pretty significant and really important.

We’ve also tied the compensation for the lowest wage worker to the highest wage worker. For example, the Foodshare Executive director can make no more than three times what our lowest paid worker makes. From now on, we’re all going to be moving forward together — if we’re moving at all.

Given that CEOs and Executive Directors in the nonprofit sector often make many — sometimes 100 times — what the lowest paid employee makes, I think that is pretty radical.

We are also really committed to really thinking about how we challenge low wages for any kind of work, not just within our organization, but within the entire sector and within the food system. One of the directors on our board is a food delivery carrier. He has been helping us think about the range of opportunities that exist to support low wage workers in the food system.

LiisBeth: Was the increase and wage compression policy a tough sell internally?

Paul: No, it wasn’t because it’s all about how we do board recruitment and who is on our board.

Traditionally boards look for directors who have certain professional designations like finance, legal, HR, or look for those with a C-suite title as a proxy for credibility, capability and intelligence. When we recruit on these terms, all we are doing is recreating the barriers that exist in society, for example, access to education.

So instead we flipped the norm on its head. Instead, we say, we’re going to prioritize recruiting board members that get the philosophical underpinnings of the organization, who have a commitment to equity, food justice, have lived experience with these issues to wisely design and implement new approaches, and who are willing to roll up their sleeves and dedicate resources to challenging those inequities.

If directors lack experience or education in certain areas, say in interpreting financial statements, board governance or investments, then we say, how can we provide support? We invest dollars in building our board’s capacity instead of expecting folks to have gone through all of the hoops that society presents to qualify, hoops that we all can’t reach.

LiisBeth: When you changed your ideas about who qualifies as a board director, did that change the make up of your board?

Paul: Completely. Today, our board is headed by an Indigenous activist, Crystal Sinclair. Our board is now predominantly made up of BIWOC folks. It’s unlike any board for an organization our size that I’ve ever seen. It’s composition really affects the key decisions that we make and how we show up in these decisions. For example, when we’re having a conversation about things like defunding the police, we’re not talking as (white) allies, we’re saying stop killing our communities because we are part of those communities. It changes how we show up on these issues, where we locate ourselves in these issues, and how we advocate.

LiisBeth: What do you think prevents other organizations from doing what you’ve done?

Paul: A willingness to reframe what it means to do the work that we do and how we do it. I think if we don’t acknowledge that patriarchy, colonialism, white supremacy, anti-Black racism are actually deeply rooted organizing principles and profoundly embedded in the way we work, well, then we will never come up with the strategies, the policies and the ideas for dismantling those systems within our own enterprises.

People need to be thinking outside of the box.

They need to be committing organizational resources to tackling these things. Tackling these things is not a black post or a black square on Instagram. Working to liberate your organization from these harm perpetuating systems requires resources, time, and a leadership team willing to be vulnerable.

LiisBeth: What advice would you give to small enterprises who are looking to dismantle patriarchy, colonialism, white supremacy and capitalism in their own operating practices?

Paul: If you want to prioritize that work, which I encourage everybody to do, and if you don’t have that capacity within, then reach out and secure a consultant that is focused in that area and has the lived experience to draw upon. And compensate them accordingly.

The second thing I would say (and this may be brutal for folks to hear) is that businesses that leverage inequality to exist are not sustainable. People have only been able to make them sustainable on the backs of low-wage workers, on the backs of precarious work arrangements. That’s the hard truth. The conversation we need to have.

I think we have to say no to building enterprises on the backs of under-paid, under-cared-for workers. If we’re not paying living wages, we are unsustainable.

LiisBeth: Is FoodShare a postcapitalist business enterprise?

Paul: Good question. You know, we recognize, capitalism is why charities exist. It’s a system that ensures that society’s resources are disproportionately distributed, and we need to be calling attention to the way that capitalism and neo-liberalism have created the conditions that cause some people in this country to constantly worry about where their next meal is going to come from while others are dreaming up new schemes to avoid paying taxes.

The existence of billionaires to us is as much a policy failure as the fact that close to a five and a half million people are food insecure in Canada.

So, unless we’re talking about how we collectively dismantle capitalism, and acknowledge and compensate for the harm that it’s caused to communities, we are just feeding a system that’s been designed to keep us so busy we don’t have time to examine the root cause of so much of the inequities that we are now all forced to navigate.

I think all nonprofit and for-profit leaders need to be holding our government to account to make sure that equity is centred in legislation and public policy

LiisBeth: Who is informing, inspiring your work right now?

Paul: I am inspired by folks connected to the ongoing Idle No More movement, folks at 1492 Land Back Lane, Climate Justice Toronto. For me, these are the groups that recognize that the voices of Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island and even across the world need to be heard. I would say I am inspired by the movement around abolition that has been led again primarily by Black women is one that dares us to dream of a world that isn’t preoccupied with punishment. Other movements that I’ve gravitated towards for inspiration, for hope, are those that are centered on justice. They’re intersectional, and they prioritize those who have had the most stolen from them as a result of settler, colonialism, capitalism, and the proliferation of neo-liberalism.

LiisBeth: Thank you so much Paul, for this interview and more importantly, for your incredible work as a badass feminist enterprise leader.

Related Readings

“Buying Black is Political”

LiisBeth catches up to BLACK FOODIE five years after its launch.

When Great Granny Inspires Great Work

A unique social enterprise that has been generations in the making tells us how to scale and build a resilient enterprise in tough times.