Publisher’s Note: We don’t often publish pieces on extreme sports, but when Lana Pesch told me about her experience I was so impressed and blown away. You’ll see themes of resilience, persistence, and hard work—all relevant to running a business. The value of having role models, discipline, and collaboration are all feminist ideas, and must-haves to be a safe and successful skydiver. This is a powerful and inspiring story and I think feminist entrepreneurs everywhere will be able to take the lessons of skydiving—who knew??—and apply it to their own endeavours. But then again, starting and growing a business is a lot like jumping out of airplanes. Am I right? You tell me. — P.K. Mutch

****

“The most effective way to do it, is to do it.” – Amelia Earhart

When the red light goes on, the door of the aircraft opens. This is still one of my favourite moments of any skydive. No turning back. Take everything you’ve rehearsed and trust yourself. Trust your teammates. Breathe.

I visualize getting to my slot. Fast is slow, and slow is smooth. Breathe. Stay calm. My focus is extreme.

Green light. Time to climb out. I move to my position for exit, not hanging onto the bar outside the plane this time, but squished in the door with an elbow jammed up over my teammate’s shoulder. Breathe. Divers are poised in a row behind me, glued to the person in front, ready to shuffle out as a unit as fast as we can. The organizer looks left, looks right, gives this whole-body visual cue—shake shake shake—then the final cue: up, down, OUT!

Together, 14 women hurl themselves out of a Twin Otter aircraft.

We have about 50 seconds of freefall to complete eight formations—breaking apart, repositioning bodies and coming together again, all between 13,500 and 5,500 feet, at 120 miles per hour (between 4100 and 1700 metres at about 200 km/hr). We fly in prone position—belly to earth—wearing colourful jumpsuits with grippers on the arms and legs so we can grab hold of each other to make different shapes in the sky. With each completed formation, we score one point. The goal is to set a new Canadian women’s formation skydiving record.

What does that take, in a male-dominated sport in which women comprise only 14 percent of membership in the Canadian Sport Parachuting Association (CSPA)?

Putting out the Call to Action

In June 2018, Marie-Ève Dallaire, 35, a stellar coach and skydiver with over 4500 jumps who has competed in skydiving championships around the world, sent out a call to Canadian female skydivers. Currently, the Canadian sequential record was set in 2016 by 42 male and female skydivers doing a three-point skydive. But there was no Canadian women’s sequential record. Dallaire invited us to try for an unprecedented performance record—and to make history.

It was a tall ask: Take a week off work, leave your family for five days, and commit to five or six jumps a day at a cost of $36 per jump for each of us, not to mention the expense of travelling to the dropzone and accommodation for out of towners. Many women could commit to two days, but Dallaire insisted on being there for the full five days—reinforcing the fact it was a team effort. From Monday to Friday we would have ample opportunity to practice, get to know each other, and achieve something special. Only 18 could commit to the week and four had to cancel last minute, leaving a group of 14—serendipitously representing the 14 percent female skydiving membership in the CPSA.

There is reason we are in such a minority. Women skydivers, says Dallaire, face far more barriers in this sport than many others. As well as significant monetary and time commitments, women often struggle to justify themselves, we are frequently judged harshly for participating in extreme sports, especially if a skydiver happens to have children. “Events like this encourage women to get involved in the sport,” says Dallaire. “It gives women the opportunity to participate.”

Women who took Dallaire up on the challenge include CPSA’s female executive director, Michelle Matte-Stotyn, who started a women’s initiatives committee that offers guidance and mentors to new female skydivers. She believes having role models is vital to growing any sport, hobby or profession, especially a sport that scares the crap out of most people. If we see a woman setting her mind to the intense physical and mental challenges of learning to skydive—and she is successful, safe, and bursting with confidence—more of us are likely to believe we can achieve that too.

Skydiving tends to attract women who are strong-willed, fit, smart, witty, fun-loving and, above all, dedicated and passionate about achieving goals. Our group was fairly experienced—no one had fewer than 400 jumps. Most of us were in our 30s and 40s. Some of us travelled hundreds of miles to take part. Still, we were an eclectic group hooked on what one participant, Christina Mercer, called “the healthiest drug in the world.”

Our crew, in part, included a chemical engineer, an acupuncturist who runs her own business, a bookkeeper, and a commercial sales director at Hyundai. Entrepreneur Stéphanie Gauthier, 43, runs a nail salon in Montreal. Her 15-year-old daughter is the accomplished indoor skydiving freestyle champion, Coralie Boudreault.

Èmilie Guilbaud, 35, who works at the Montreal Chamber of Commerce, took advantage of any weather interruptions to play Nick Waterhouse’s Katchi about 800 times so we could all learn the floss.

Mercer, a 37-year-old nurse with a military background, was still breastfeeding her six-month-old baby, which she did between jumps and during dirt dives—the walkthrough rehearsals we did on the ground before taking to the sky. She also brought along her other two kids, both under the age of five, as well as a nanny, a novice skydiver. Having her kids and nanny along was the only way Mercer could participate.

I answered the call because Formation Skydiving is my passion. I love the concentration and discipline required in working together to build a formation. It’s intoxicating. I love flying my body at terminal velocity to get in position: de-arching my body to cup air and slow down or punching out my hips to go faster. Such subtle and precise movements in extreme conditions, all while following a completely different set of rules to moving on the ground. I love the focus required, to breathe and stay calm, while flying at 120 mph with adrenaline coursing through my veins. And it’s rare and special to have an opportunity to fly with women only.

Despite my bank account being a little thin to take a week off freelance work, I jumped in my car along with my Toronto skydiving sister, Alanna Adleman, 29, a project manager in the tech sector currently between jobs. We packed sleeping bags, a foam roller, enough food to last three weeks, drove 600 kilometres to Joliette, Quebec, and bunked in a trailer on site, splitting the costs.

Hitting the road for a record

Attempting to set a national record was far off my radar when I took up the sport eleven years ago. Then, I was looking to escape the stress of the city, my job as a producer and a recent break-up. So, when a friend invited me to join her for a weekend in Niagara to watch her skydive, I readily accepted. Then, out of the blue, as she turned off the highway towards Skydive Burnaby, I said, “Maybe I should jump.”

Judy smacked the steering wheel with both hands, then slapped me in the shoulder. “Of course you should jump!”

I signed up for a tandem skydive: I would be attached by harness to a licensed instructor. My preparation included watching a video and getting some ground training from a man who would become my husband. Later that day, I leapt out of a Twin Otter aircraft from an altitude of 13,500 feet with almost a minute of freefall. Just before taking that leap, I felt a sense of my own mortality—combined with an all-encompassing vitality. I was both terrified and charged with anticipation. Then I stepped out of the plane and flew. It was breathtaking, exhilarating, wildly free. Everything else in the world—stress, anxiety, worry—fell away. I had no choice but to be present. I was hooked.

As we sat around a bonfire later that night, I realized I hadn’t felt so calm and peaceful in a long time. I sensed a beautiful camaraderie among the skydivers—accepting and open. I felt welcome. I also noticed there were some kick-ass women who had an unspoken bond between them. I wanted to be one of them. I wanted to join this club of risk takers who were living on the edge, but also holding down real jobs and responsibilities. Suddenly, all the issues that had been overwhelming me felt small. What I wanted most was to be back in the sky again.

In the eleven years since, I’ve done 450 jumps, not a lot for that length of time in the sport, but there is no right or wrong path in skydiving. You do what you can and in a way that you want. During the first few years, I averaged 30 jumps per season, but increased that in 2012, the year my dad died. It felt like the right thing to do.

Skydiving has taught me to be less afraid, more humble, and to take more risks in other areas of my life. For example, the sport gave me the confidence to take up running, a sport I once loathed, and last year I ran a half-marathon. I risked writing fiction, weird dark humourous stories that I thought no one would want to read. And then I got a book deal.

In preparation for the women’s record, I did as many formation jumps as I could and honed my skills by skydiving indoors over the winter at iFLY Toronto. Incidentally, I won a gold medal in the 4-way FS intermediate category at the 2018 Canadian Indoor Skydiving Championships.

So when I arrived in Quebec to attempt a national record, I felt ready for the challenge.

DAY ONE

Under ideal skydiving conditions—blue skies and low winds—14 of us gathered together in a sheltered outdoor packing area of Voltige.

Dallaire gave a pep talk and welcome speech, and stressed how the week was going to be about teamwork and discipline. And fun, of course. Certainly, we each had our own personal reasons for participating, but, overall, we were there to achieve a TEAM goal. Together, as a collective, we set that goal: a 14-way, all-female, formation skydive that would score at least eight points.

The pilot piped up, if we made nine points, he would buy the beer.

By 10:00 a.m. we had zipped up our jumpsuits and were practicing the first dive plan on the ground, what’s called dirt diving. We practiced the order of entering and exiting the aircraft as well as the formation we would make in the sky about a dozen times. Then we put on our rigs—the backpack that contains our parachute and also a reserve chute—so we would visualize who would be where in the sky, and what colours to look for, and rehearsed a few more times. A bigger goal than the record was keeping everyone safe. In addition to the dirt diving, we did repeated gear checks to ensure the correct placement of all buckles and straps, and both main and reserve closing pins. There were zero malfunctions or injuries through our 20 skydives that week.

Then it was time to fly. Our energy in the plane as we climbed to altitude was bright with anticipation. But we were dead quiet, immersed in our own visualization process: going over the exit, the dive plan, deployment and emergency procedures. That’s all standard, healthy skydiving practice.

Just prior to jump, five of us, plus our videographer Dan Lepôt, climbed out and hung onto the outside of the aircraft. That’s anticipation at an extreme level, requiring 100% focus. We all watched for Dallaire’s visual signal—a full body jiggle, then watched her final cue: up, down, OUT—all she could manage while wearing a helmet with a full-face visor. We exited as a group as close together as we could and became a chunk of bodies flying through the air at 13,500 feet.

We had about 50 seconds to complete our dive plan then, at 5,500 feet, women on the outside of the formation tracked away like Superman—or Superwomen rather. They turned 180 degrees and made their bodies into human arrows—straight legs, flexed thighs, clenched abs, arms at sides, cupped palms, pointed toes, rounded shoulders—shooting as far away from the group as possible before deployment, so everyone could open their chutes in clean air. The second group tracked away at 4,500 feet and then all of us deployed our parachutes at 3,500 feet, a standard altitude for a group of our size and caliber. Leaving deployment too long increases the chance of ground rush, the illusion of the ground abruptly rushing up to meet you, which creates a terrible, panicked feeling.

We managed to score four points on that first jump. Not bad for 14 people who had never jumped together before, but we had work to do. We completed four more jumps, following up each one with a video debrief and notes on where we could improve—finessing a myriad of details from the position of hips or bending of elbows, to reaching for a grip and staying close to the formation.

The goal that day was to get to know each other’s abilities, establish our fall rate as a group since we were a variety of heights and weights, and find out where people might feel more comfortable. All positions require specialized skills—floaters who start outside the plane need to track up; the base who are second to exit need to be stable and provide a solid centre for the formation; and divers who are last out and need to, well, dive like a bullet to catch up to the group.

It was a solid first day and that night I slept like a rock.

DAY TWO

We only got three jumps in before we were put on weather hold due to rain. During debriefing, we poured over how we could make our next jump better than the last. Or “Try to suck less,” is how one of my Burnaby friends puts it.

We also used the rain delay to have a round table discussion on our experiences as women in the sport. Mercer said that knowing it was an all-women’s event reassured her that she wouldn’t be judged for bringing her kids and a nanny along or breastfeeding between jumps. “You live your life for your children, but you can’t stop living your own life. I want to show them the world. I hope my girls jump someday.”

She added that she also finds herself constantly defending the safety of the sport, pointing out that skiers, horseback riders and hockey players all risk breaking bones and getting concussions. Even driving a car may prove more life threatening given fatalities in road accidents. Dropzone.com hosts an unofficial database that reports six skydiving fatalities in Canada in the last five years. In the province of Ontario, Canada alone, 341 people died in highway accidents in 2017.

Our skydiving coach, Dallaire, also a mother of three boys, said she’s been asked, “When are you going to get a real job?” It’s a question her partner, a pilot, never gets.

Daniel, our videographer, chimed in to describe the vibe of the all-woman’s event as relaxed and joyous. “There is a lot more laughing and dancing!”

DAY THREE

As usual, we gathered at 8:00 a.m. with jumpsuits on to rehearse our first dirt dive. But weather was against us again. We managed just one jump—but scored six points!—before a downpour grounded us. We waited it out by chatting, napping, eating, then dancing.

The weather cleared by 1:00 p.m. and we scored seven sweet points on jump number two – just a point away from our goal!

But that afternoon, our energy started fading. Formations that should have been easier were becoming more challenging. Something was off. We were overthinking things, losing focus, making novice mistakes. We did five jumps in total and debriefed after the sunset load.

Dallaire encouraged us to get a good night’s rest. Were we being too hard on ourselves? Of course. But we wanted to prove to ourselves and others that women are capable of extraordinary things. The eight points had become the symbol of that collective goal, and now we desperately wanted to achieve it.

DAY FOUR

The weather cooperated for our first two jumps, which were solid, with better flow than the day before. But we were still making small mistakes.

Third jump in we scored seven points, again. But we were back in tune with each other and having fun. “This aircraft smells incredible!” the pilot said. Well, that’s what you get when the plane is full of women!

The fourth time, while climbing to altitude, our energy was buzzing, palpable. We were focused. Confident. Driven to nail that elusive eighth point.

The jump itself had the rhythm of a heartbeat. Natural and calm, with the exact right amount of anticipation. Precise grips. Fast was slow and slow was smooth.

Our formation built from the centre out. I was part of the base and needed to approach fast but in control. Only then could I reach out and grab hold of my teammates’ arms. Once we had formed the base and were flying stable, the outer group could latch onto our legs to create the first pattern. We all had one responsibility: fly our slot, and fly it well. For everyone to stay on level in our group of all shapes and sizes, we had to make adjustments as each person joined. For instance, along with the rest of my gear, I strapped on twelve pounds of weights in order to fall faster to get in position to form the base.

As soon as we created one design, Dallaire gave the key—an exaggerated head nod—and we all let go of our grips, then moved swiftly into position for the next pattern, and latched on again. Eight times in total, requiring hundreds of small precise movements carried out while traveling 120 mph, belly to earth.

After we all landed safely, we broke into wide grins and exchanged hugs and high fives. We felt we had nailed the record but had to wait for the videographer to send proof to the CSPA judges—and await their final decision.

We did two more jumps that day, but couldn’t top our performance.

DAY FIVE

The weather crapped out again, limiting us to just one more jump but, right after, we heard back from the judges: We popped the bubbly. We hugged, laughed, cried and danced to our theme song, as if we had known each other years, though it had just been five days.

We also got national media coverage for the record: Here’s the video of the jump, and the story on CBC.

Taking in What it Means for 14 Women to Jump for a Record

When I got home and started to recount the stories of our week to my husband, I was brought to tears. The hashtag #girlpower sums it up but doesn’t capture my sense of pride and accomplishment—what I imagine my 13 skydiving sisters feel. We made history in our sport and proved how pushing your boundaries, discipline, and teamwork can pay off. We set a big goal, worked hard to achieve it, and gave each other support, respect, and encouragement that made us all stronger—individually and together as a team. At the end of the day, a record is just a record unless it does what we hope for most: Inspire women to set big goals and join forces in extraordinary communities to get support and achieve them.

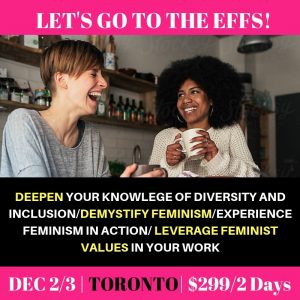

For more inspiration, consider attending the upcoming Entrepreneurial Feminist Forum!