Several weeks ago, a 35 year-old, Latinx, queer, immigrant woman-in-tech entrepreneur named Sophia Stone did what entrepreneurs do: apply for funding.

With her 65+ page business plan well underway, Stone applied to, among other prospects, Futurpreneur Canada (Futurpreneur) a 20 year-old government-funded Canadian nonprofit that provides up to $60,000 in financing, along with mentoring and coaching to youth entrepreneurs 39 and under.

Stone expected the usual hoop jumping that comes with applying for a loan. She did not expect to find her herself in a high-stakes face off with institutionalized racism.

Stone publicized her experience in a Medium post on Aug. 5. Frustrated with her interactions and response from Futurpreneur, Stone called me. Her story clearly demanded further amplification. We believed this story also held important lessons for incubators, accelerators; in fact the entire entrepreneurship support industrial complex. With Stone’s consent, we began our own investigation.

Let’s start at the beginning.

A month after filing her application to Futurpreneur, Stone was engaging in an Instagram discussion with a fellow Latino about Latino proximity to whiteness and the privilege that affords. “We as a community need to also face the anti-Black racism that occurs with us too,” she wrote.

An interloper, who is not Latino, happened upon the discussion, and fired back with racist insinuations, which Stone and others challenged.

Stone, outraged by his comments and as good millennials do, did some internet sleuthing. Who the hell was this Dick? Who did the Dick work for? To her shock, she discovered he was a mentor at the very place she was applying to—Futurpreneur.

He was university educated, successful, midling, millennial white tech entrepreneur. Along with being a youth mentor at the very prestigious Futurpreneur, he sat on the advisory board at The HUB, a Scarborough based startup incubator at the University of Toronto.

Genuinely concerned for the safety of herself and other BIPOC entrepreneurs, Stone made the gutsy decision to bring Dick to the attention of the CEO of Futurpreneur. Stone was hopeful something good would happen out of this. However, the official email response and “courtesy” phone call in response to Stone’s complaint that the email received was inadequate, revealing that despite commitments to diversity and inclusion, actual policies, protocols and practices remain deeply racist, sexist and oppressive.

The CEO explained they had investigated Dick, spoken to him and the four people he had mentored (one a person of colour, though not black) and found that, while they strongly disagreed with his point of view, Dick is an exceptionally good guy who is just underinformed, believes in equality, and that there was “no hint that his actions are inconsistent with our values of diversity and inclusion.” And if there was a whiff of stench, it appeared to be an isolated incident. Since Stone was not yet at Futurpreneur, her concerns hardly mattered, insinuating they were going above and beyond by taking any action at all. And, besides, Dick wrote these things on his own social channels—not Futurpreneur’s; how could they be held responsible for what he or any of their other 3000+ volunteer mentors do in their personal time? To cover all bases, management brought the issue to the attention of the board, which by the way, included a Black member (new, her first meeting was July 14/15); the collective decision was made to continue working with Dick, albeit asking him “to be mindful of his public comments” and to do a bit of recommended reading. If there were future incidents, they promised to review his role.

The CEO then proceeded to remind Stone about all the good diversity and inclusion (D&I) work Futurpreneur has been doing, including promoting their IT Director (a Black man who has been with the organization for five years) to Head of D&I, as well as the recently added Black board member.

Our Follow Up Investigation

I found Dick easily on LinkedIn. He refused to meet and tell his side of the story, responding in writing that he did “not see how my (his) personal posts have anything to do with Futurpreneur.”

I interviewed the CEO of Futurpreneur. The Chief Experience Officer joined the call. The CEO professionally conveyed the same discussion points relayed to Stone. During the call, I discovered the organization had not seen or read Dick’s recent 10,000-word essay including carefully researched citations entitled “Evidence-Based Examination of Systemic Police Bias in the United States,” arguing that he is right, everyone else is wrong, and that police bias does not exist and that the inherent badness of Blackness brings on their troubles.

This essay was published for all to see, under his real name, several days after his meetings with Futurpreneur.

Futurpreneur thought they had handled it. Case closed. But racists don’t just change their deeply held beliefs after a meeting. Once Futurepreneur read the Medium post, to their credit, the organization called an emergency meeting and, later that evening, announced that Dick was no longer affiliated with Futurepreneur. The CEO wrote and posted this blog piece on their site the next morning: “We made a Mistake. We Fixed It. Now We Learn From It and Move Forward”. That was Aug. 6.

Meanwhile, three days earlier, the Director of The Hub at U of T learned about Dick’s posts independently from staff. The very next day, that organization terminated Dick as a member of their advisory board and posted this note on their website, immediately: “Comments like those made online stand in sharp contrast to the University of Toronto’s commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion.”

With Dick removed from both organizations, Stone, at this point, might be pleased. She was not. “This story was never about the mentor,” she wrote in an email to me. “It stopped being so the minute (Futurpreneur CEO) Ms. Greve Young chose to protect a racist. She is complicit in this story and used her own racism as a tool to systematically perpetuate institutionalized racism. She fixed and learned nothing and is wholly unfit to lead this organization.”

Futurpreneur’s mea culpa post never mentioned Stone’s role nor honoured her courage for speaking or acknowledged the weight of the emotional labour people of colour bear when they risk calling out a racist in their midst. They most certainly did not thank her for the personal risk she took.

Not doing so sends a clear signal to other marginalized, community whistleblowers: if you speak up, be prepared to be re-traumatized. Organizations may mean well, but they clearly lack the know how to deal with complaints about systemic oppression—and their ham-fisted action can, itself, be oppressive.

Calling in White Leaders in Entrepreneurship

So what can we all learn from this? And by “we,” I mean everyone, including our team at LiisBeth?

Make this Two-Handed Work: We must advance diversity and inclusion organizationally but, as importantly, dismantle racism and other systemic forms of oppression in broader society. That starts with accepting that we have all been raised in patriarchal, capitalistic, colonialized societies based on white supremacy—we are totally brainwashed. Ergo, so is our ability to “see” and respond appropriately if our goal is to dismantle systemic oppression. What to do? Make sure you have relationships with anti-oppression activists (perhaps even on your board). Recognize and check in with your own racism (we are all racist) when called to deal with immutable racists in your midst. Seek out, support and establish relationships and work with leading activist organizations—not just corporate consultants who do this work daily on the ground and are farther along in their liberation journey than you are.

Know the Law: Incubators and accelerators depend on volunteers. But few have clear intake protocols, onboarding workshops, and explicit policies around volunteer conduct and accountability—let alone transparency about what happens if that conduct breaches policy or damages reputation. It is incorrect to assume what someone says on their personal social media channels is not your business. According to legal precedent, organizations have, can and should hold employees and volunteers legally responsible for what they post on their personal social media channels. Especially if it causes reputational damage, harm to the community, or contravenes an organization’s stated values.

Develop anti-oppression informed policies and practices : The investigation process itself and fact that Futurpreneur exonerated Dick the first time raised a lot of questions and suggested a racist perspective, and perhaps even white feminist lens was at play. For example, how many times does someone have to demonstrate racism before being held accountable by an organization that is committed to diversity and inclusion? How are you treating the whistleblower? As an annoyance? Or are you honouring their identities, courage and wisdom by truly listening and figuring out how to overcome the challenge together, in a way that is anti-racist, anti-colonial and anti-patriarchal? Are you using the fact that you have a Black or Indigenous board member as a cover or leveraging their wisdom and experience in a meaningful way? In this case, it might have been more appropriate to fully engage person of colour on staff, the person in charge of D&I, or BIPOC person on the board to participate in calls with Sophia—and me—rather than a white male colleague.

Be Clear About Tolerance Level: If a person kills someone, do we wait to see if they kill a second time before we act? Can you really change a person’s “misinformed” beliefs by handing him a few readings and telling him not to do it again? Dick’s Medium post written to prove he is right and everyone else is wrong—after reprimand—reveals the need for a clear zero tolerance policy. Does this lead to “cancel culture”? If you think that cancel culture is really a thing, think again.

What Now?

Ultimately, this story is not about Futurpreneur. It’s about how to make real change.

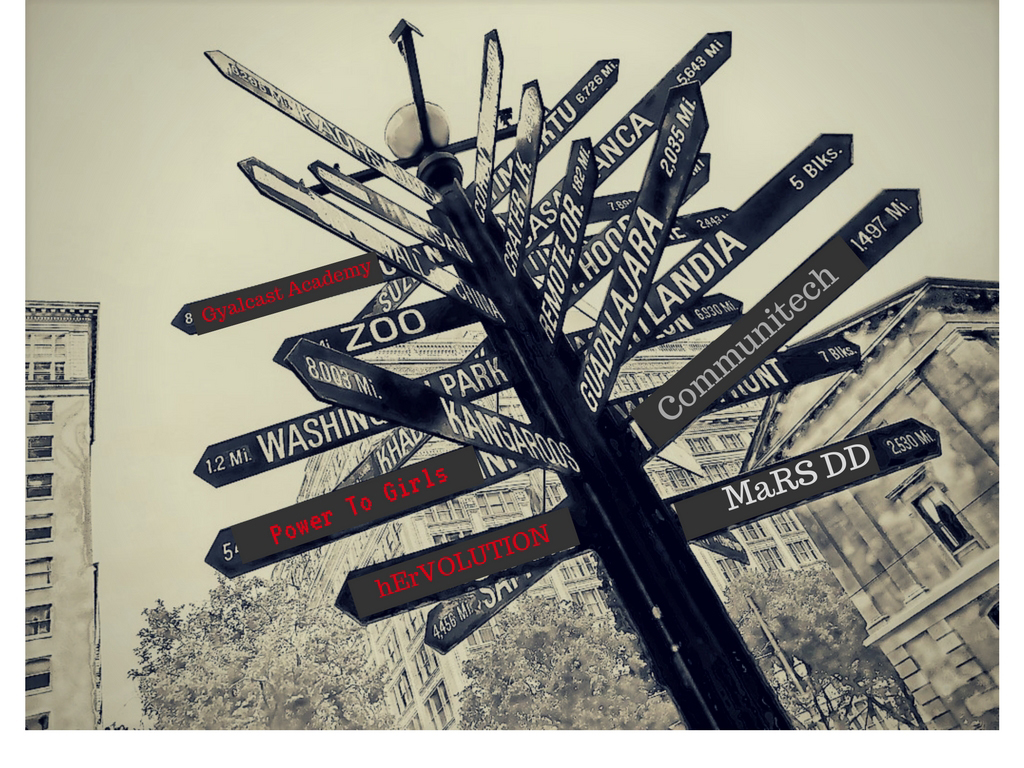

The fact is that our entire, mostly government funded entrepreneurship ecosystem is patriarchal, racist and pro-extractive capitalism centered. If we want to see a healthy post COVID-19 economy and socially just world emerge, this must change—fast.

Through this debacle, Tara Everett, a young Indigenous entrepreneur and sixties scoop survivor contacted me. She told me that she pursued entrepreneurship after tiring of repeated discrimination in the job market only to experience further discrimination and trauma in the entrepreneurship space. The problem, she said, lies with programming at entrepreneurship centres, which is defined by government policy rather than being “led by the people who need to access these services.” Everett left me this to think hard about: “I believe at the heart of it, it wasn’t the people that I felt the discrimination from. It was the policies and the procedures.”

Last year, a June 2019 report, “Strengthening Ecosystem Supports for Women Entrepreneurs,” surveyed 117 Ontario entrepreneurship support organizations and found that more than 68 per cent of startup incubators do not provide training on gender equity, diversity, and inclusion. A mere 3.4 per cent of incubators make accommodations for specific demographic groups. Worse, only 20 per cent of the 686 incubators and accelerators operating in Ontario even bothered to participate in the survey.

The vast majority of our mainstream women’s entrepreneurship centres and institutions are still led by white women and predominantly white boards of directors. Open positions are still filled primarily by white men and women. The Aug. 11 “State of Women’s Entrepreneurship in Canada 2020 Report” by The Women’s Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub (WEKH) at Ryerson University affirms that as a nation of white, settler, colonialists, neo-liberal capitalists with dominant patriarchal norms and systems, “bias is baked in” to everything we do and create. Wendy Cukier, Director of WEKH noted in her webinar presentation about the report that “diverse women face additional barriers in our entrepreneurship ecosystems. As long as our definition of innovation and success is predominately tied to tech and science, we will continue to see exclusion for all women.”

This year, the York Entrepreneurship Development Institute (YEDI), was recognized by the University Business Incubator (UBI), a global ratings company, as one of the “World’s Top Five” business accelerators. Yet, a look at YEDI’s website shows that the place is overrun by white men. Out of 45 mentors, instructors and staff, only seven are women (15.5 per cent), and a mere three are from visible minority groups (.06 per cent). There are no Black mentors.

Several folks advocated for UBI to change their assessment criteria to include D&I metrics, including me. The response? Economic performance is all that matters. As a result, to me, UBI recognition means “seal of patriarchal approval” versus excellence.

This is a moment to seize and learn from, to build a movement.

If our entrepreneurship support institution leaders continue to lag and receive funding, it is up to us—the entrepreneurs they serve—to rise up and push for more meaningful progress.

Some Additional Next steps?

First, let’s applaud Sophia Stone for her unbelievable, selfless courage. You can show your support by taking the time to read her own story here. I guarantee you will learn from it.

Futurpreneur should also step up and thank Stone for this incredible learning opportunity she handed them, and also clarify how her work as a whistleblower will impact her application to Futurpreneur going forward—should she decide to continue.

Entrepreneurs and small business owners everywhere need to continually assess their own prejudice, practices and policies. Myself and LiisBeth included. Because committing to diversity and inclusion is an ongoing, living, complex personal and professional practice, not a statement.

In fact my own white feminist lens came into play while working on this article. I too have learned some hard lessons.

Related Reading

How Do We Remake The World?

The first-ever SheEO Global Summit featured 93 speakers which offered new strategies to over 600 participants including Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Gaslighting: The Silent Killer of Women’s Startups

With $150 billion of economic growth at stake, can we really afford to keep gaslighting women entrepreneurs? What can you do to help stop it?

Where are the Women in Canada’s Women in Tech Venture Fund?

The Women in Technology venture fund administered by the Business Development Bank of Canada is betting that bigger is better -and that just one woman equals change. But does it?