I wear many hats. Journalist. Editor. Instructor. Youth and community program facilitator. Entrepreneur. Of all the titles, it’s the last one that I feel the most conflicted about claiming. Entrepreneurial certainly describes my spirit and journey: Thirteen years ago I incorporated a company, which my business partner and I have been running ever since; I have spearheaded several grassroots community initiatives and programs; and for the last two and a half years, I have been fully self-employed, meaning I pitch and land myself work or I don’t eat.

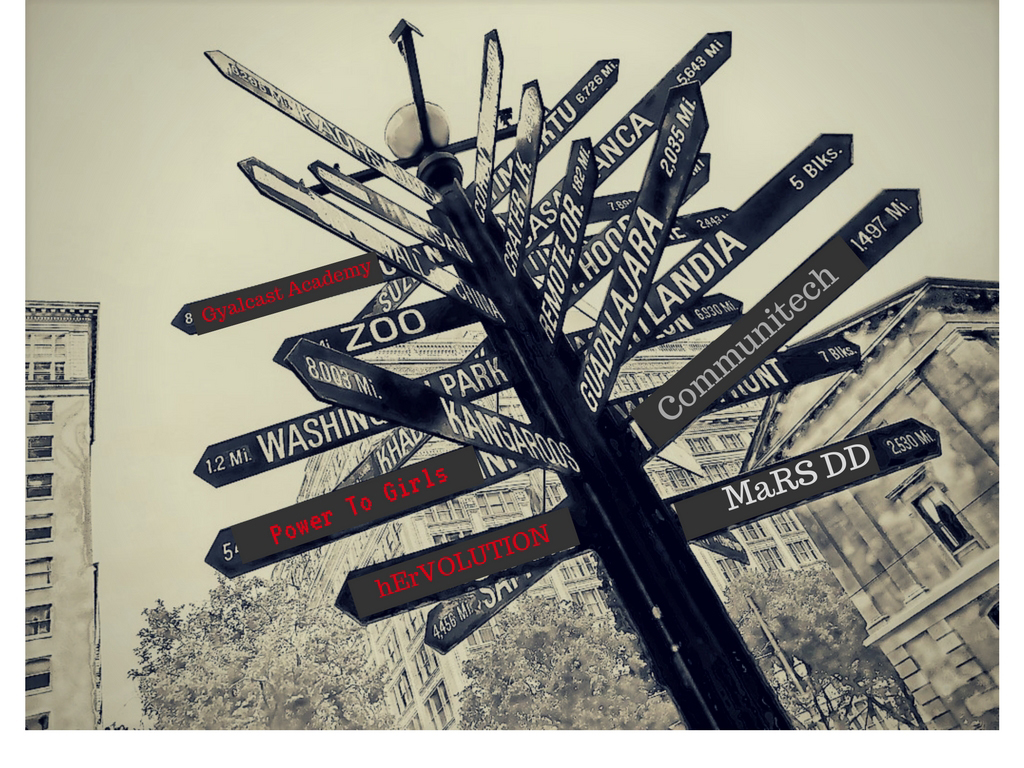

However, when I think entrepreneur—perhaps because of the magazines and books I’ve read, podcasts I’ve listened to, and representations I’ve seen on the topic—I largely think of a world to which I don’t belong. That world is rich with incubators, accelerators, networking mixers, co-working spaces, venture capitalists, angel investors, and Dragons’ Den-style pitch competitions. It’s not a world I was ever a part of (more on that here). Now, as I’ve aged out of the under 29 demographic and realize many others experience similar challenges to mine, I find myself wondering what it will take to bring more young women of colour in Ontario into that entrepreneurial world.

In November 2015, Ontario announced a $27 million investment in youth entrepreneurship as part of its larger $250 million Youth Jobs Strategy. The initiative includes a youth business accelerator program, which provides training to youth starting technology-based enterprises; a youth investment accelerator fund to provide financial and business skills training for startups; and campus-linked accelerators to help colleges and universities provide entrepreneurship resources for students and youth in their regions. The government is partnering on this project with the Ontario Network of Entrepreneurs (ONE), a regional network of 90 centres across Ontario that provide in-person and online advice, funding, resources, and programs for people who want to start and grow successful businesses.

Much more than when I was starting out, the idea of “youth entrepreneurship” is catching on like wildfire. I am excited about this. But, from my own experiences, and those of people in my networks, I know that to ensure that these government-funded initiatives are inclusive, welcoming, and accessible—specifically for racialized women—it will take more than just dollars and cents. To find out what it will take for the government-funded startup space to serve racialized women better, I spoke to several young women entrepreneurs, the same ones from part one of this article, as well as women behind innovative entrepreneur-serving initiatives.

Ensuring Access

The word access comes up again and again in my conversations about what government-sponsored programs must consider when setting up initiatives to help young women of colour entrepreneurs. Doina Oncel, founder of hEr VOLUTION, a non-profit that aims to increase access to innovative education and employment services for young women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), says it’s important for these programs to listen to what young women need. To create hEr VOLUTION’s hv Think Tank Accelerator, which launched this past summer, Oncel drew on her own expertise having worked in social services, as well as her own experiences launching a business while living in a shelter for women and children who are victims of domestic violence. The four-month program, funded by the Ontario Trillium Foundation, is geared towards young women 15 to 26 years old who are interested in entrepreneurship and face barriers. For example, they may be in conflict with the law or new to Canada or from a low-income household. Topics covered include public speaking, financial literacy, marketing, and business planning. “[Having] worked with this demographic, I understood that they have a lot of great ideas, they just don’t know where to go [for help],” Oncel says. “When it comes to entrepreneurship learning, you have a lot of programs available in the city, but in the ‘priority neighbourhoods,’ there aren’t a lot of programs.”

Aisha Addo, 24, is the founder of the Power to Girls foundation, a non-profit she started at 17 to “empower Afro-diaspora girls in the Greater Toronto Area and abroad,” and most recently, DriveHER, a ride-sharing service that’s like Uber but focused on providing safe rides for women. She points out that because so few programs are offered outside of the downtown core, barriers to access can include things like not having transit fare or the lengthy travel time to get to an accelerator or incubator. She also criticizes many existing programs for not doing enough outreach within priority communities. It’s one thing to have programs available, but the work doesn’t end there. It’s important to ensure that access isn’t limited to a privileged few, especially when government funds and a social justice mandate are at play. “If the people that are actually going to benefit from the program do not know about the program, you’re not really doing anyone a service,” says Addo.

Kristel Manes, director of Innovation Centre at Innovation Guelph, has spent the last three years researching the experiences of women entrepreneurs in southwestern Ontario. The research led to the creation of The Rhyze Project, a women’s entrepreneurship program that focuses on building self-esteem and self-confidence as well as the development of a soon-to-be-released training tool that will better equip mentors to serve clientele at business and innovation centres. She says outreach can be difficult and is a “never-ending job,” but advises other innovation centres to follow her lead. She says Innovation Guelph connects with the community in genuine ways at all levels ranging from sitting on several organizational boards to being present at libraries, community centres, and cultural events. Still, she admits it’s “hard work trying to get to everybody.”

Beyond outreach, making accelerators more accessible means making more options available that consider the varied experiences of young entrepreneurs, Addo says. For example, many accelerators she has come across require a full-time commitment, something she hasn’t been able to make due to her job. Or too often, incubators focus on developing tech businesses, like Ontario’s youth accelerator business program. “What happens if I’m not doing tech?” she asks.

Increasing accessibility also means having women of colour represented among the facilitators, programmers, and administrators of these initiatives. Lamoi, a 33-year-old spoken word artist and founder of Signature of a Mango jewellery from Brampton, Ont., says the number-one way to ensure engagement from women of colour is to have them at the helm of creating and delivering the programs. “We have a whole different life experience, even if we don’t all come from the same place,” she says. “The experience of non-white women is so completely different and especially now at a time of extreme racial tension and micro-aggressions.”

Creating Safe, Supportive Spaces

It’s this sentiment—that representation matters in incubation spaces—that Chivon John saw manifest when she founded Secrets of a Side Hustler (SOSH). It’s an organization that supports people who start and grow businesses while working full-time, a type of entrepreneurship increasingly popular among young people, according to Julia Dean CEO of Futurpreneur (formerly Canadian Youth Business Foundation). John says that about 90 per cent of the audience at her events are women of colour. She did not intend that when she started out, but she’s very proud her organization has drawn out this demographic. She attributes it to the fact that other women of colour likely gravitate to what they identify with. Someone who looks like them and may share a similar story is a rare occurrence in traditional entrepreneurial spaces. “I’ll go to lots of events and I don’t see as much of the diversity,” says John. When she recently travelled to Hangzhou, China, as one of 30 Canadian delegates selected to take part in the annual G20 Young Entrepreneurs’ Alliance Summit, she was the only woman of colour in the group. “There’s lots of great things that happen within the city, but it’s disappointing when you go and you don’t see somebody that looks like you,” she says.

Lack of representation led 27-year-old Alicia Bunyan-Sampson to create the Gyalcast Academy, a new six-week workshop series for young Black women who identify as creatives or entrepreneurs and live in one of Toronto’s underserved or “priority” neighbourhoods. She says it was imperative to build a space that acknowledges the layered experience of being a Black woman, and she grew “tired of waiting for a white guy who doesn’t understand us anyway to make it.”

From what she has seen, most entrepreneurial spaces are not created with women of colour in mind. She is often left thinking, “How are you running a community program for young entrepreneurs and not offering free tokens or food or child care? Why do I have to navigate through sexism and racism in a space that you claim is for me? Why is this space/resource adding more stress to my already stressful life with these unrealistic expectations of me?”

These are all factors she considered when building Gyalcast, a program that combines skill-building and mentorship with a self-care component. The world does not encourage Black women to be soft with themselves, Bunyan-Sampson explains. As someone who struggles with the application of self-care in her own life, she felt it was essential to include it within the program.

Janelle Scott-Johnson, a 24-year-old creative photographer and solopreneur who participated in the academy, says she found the self-care component especially effective. It’s something that was absent from a mainstream campus-linked accelerator she previously attended. Participants have time to speak openly about any negative issues they are facing, she explains, and share tips on how to navigate them through things like meditating or keeping a journal. It’s something women of colour need, Scott-Johnson says. “There are not a lot of spaces like that where you can actually talk about things that are bothering you and have a room full of people that won’t judge and will teach you ways to care for you and your mental and your physical [well-being].”

Gyalcast was an “amazing space” that Scott-Johnson felt she belonged in. “I feel like the people who started that up, they can relate to the participants,” she says. “They are women of colour, they are Black, they’ve been in my position trying to start up, and they provided the key things we need.”

This was intentional in the program’s design. “We need to create our own spaces to ensure they are safe,” Bunyan-Sampson says. “Spaces organized by people that look like you are important, and it’s something not a lot of people talk about.”

Moving Forward

When I look around my networks, I see no shortage of young women of colour with entrepreneurial ideas, spirit, and passion. Many of them have already started one or more businesses. What I do see is a shortage of capital, resources, support systems, and opportunities for growth and sustainability. Ontario is putting resources into youth entrepreneurship, and even women entrepreneurs, with the Women Entrepreneurs Ontario Collective, which is putting forth recommendations on how the province’s economy can be strengthened through strategy focused on women entrepreneurship and innovation.

But it’s important not to overlook systemic racism and implicit bias, and their impacts on the startup space, by taking a one-size-fits-all approach to entrepreneurship. It’s also important to remember that it’s not as simple as throwing funding at underserved communities. As Scott-Johnson cautions, ingenuity is easy to detect. Organizations chasing after funding dollars and setting up programs in communities that facilitators don’t know well simply doesn’t work. “It’s hella obvious when someone’s heart is in it and when it’s not,” she says.

Though the research is non-existent on young racialized entrepreneurs in Canada, we can combine anecdotal accounts with studies from the United States to arrive at some conclusions about possible solutions to this complex problem.

The large incubation spaces that are currently receiving serious money to help enterprises scale up need to improve outreach and access to underrepresented groups such as young women of colour. The key to this is increasing the number of women of colour in leadership roles within these organizations and structures. Remember, representation matters.

At the same time, the government needs to consider allocating funds to support the work that’s already being done by organizations such as Secrets of a Side Hustler and Gyalcast Academy, which are already effectively engaging this demographic. Ontario seems to be doing a little bit of this with its Strategic Community Entrepreneurship Projects program, which offers funding, resources, and training to people 15 to 29 years old starting a business through partnerships with community organizations. Some have specific service mandates, such as the Bimaaji’owin Anonidiwin project in Thunder Bay focused on Aboriginal youth, or the Vulnerable Somali Youth Entrepreneurship Program in Toronto’s Etobicoke area. It’s this type of demographic-specific approach that is more prevalent in the U.S.

Work also needs to be done to bridge the gap between small and large startup spaces. Manes told me that part of Innovation Guelph’s outreach strategy involves being known amongst referral sources, mainly professional services for small business owners (lawyers, accountants, insurance providers). Why not have grassroots, community-specific incubation spaces partner with larger accelerators and incubators and referring participants, sharing resources, and exchanging knowledge?

Emily Mills, founder of How She Hustles, a network of 5,000-plus diverse, social media–savvy women who “hustle,” however they define that word, is positive that there is much to be gained on both sides. A serial connector of people, Mills is interested in figuring out a way to create a meeting of the minds, a space where an older white professional woman can meet with a young racialized entrepreneur and learn from each other. Young women may yearn to understand the business world, she says, while older women may benefit from diversifying their network to remain relevant, find talent, and develop new ways of doing business. “There is a benefit if those two worlds can come together.”

Related Reading: “Not Your Incubator’s Entrepreneur (And That’s Your Loss)” by Priya Ramanujam