India is a country where tradition and modernity continue to collide and clash. The government, and those who fight for progress work hard to increase gender equity and equality. However, financial independence is a critical enabler in the advancement of women’s equity and equality in India. Given the grim situation today, financial independence seems miles away from being a possibility for India’s women.

Here are some of the reasons why:

Education is discouraged

Education offers the best opportunity for women to find employment, provided it continues to be encouraged. Since 2010, India has provided free education for every child until 14 However, not being compulsory, children have the right to education but not the obligation. Many girls do not find themselves in classrooms because their parents prefer to educate their sons. Girls are forced to help with housework. Women have persisted against all odds, and are now getting an education, and a way to becoming financially independent. With this change, the term ‘gender equality’ has grown increasingly popular in recent years. However, there is a significant number of people here who are unable to distinguish between gender equality and gender equity. Gender equality refers to outcomes that are equal for all genders. Gender equity acknowledges that women and persons of different genders do not have the same ‘starting position’ as men.

Cultural barriers to independence

We in India endorse the ‘Educate the Girl, Save the Girl’ campaign. Yet, sadly, a university degree is nothing more than a piece of paper used to entice a suitable groom. Many are educated with the sole purpose of getting husbands, not to join the workforce. In Gujarat, I visited a few marriage bureaus. It came as no surprise to learn that upper-middle-class families prefer a female who is well-educated, but willing to leave her job (which requires commitment and time) after marriage. Allowances are made if you want to work from home, but it’s usually to create the impression that the ladies are suitably engaged. If a boy comes from a middle-class home, he is receptive to marrying a working lady, but not at the expense of housework. They’re aware that for any woman to perform both duties well without assistance is challenging. It’s best for all if the woman is a full-time housewife. Thus, many educated women who could be national treasures are staying at home, which leads to dependence on husbands for the rest of their lives.

Cleaning jobs and similar low-paid jobs are considered menial and do not provide women with dignity. It’s a point of contention whether women who are highly paid receive more respect. In 1972, Ela Bhatt started The Self-Employed Women’s Association https://sewabharat.org – SEWA. The name means ‘service’ in numerous Indian languages. It is an Indian trade union founded in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, that advocates for the rights of low-wage, self-employed women. With over 1.6 million participating women, SEWA is the largest organization of informal workers in the world. SEWA is based on the idea of complete employment, through which a woman can provide food, health care, childcare, and a safe place to live for her family. This stellar organization has transformed innumerable women’s lives. Giving them what women need most – financial freedom.

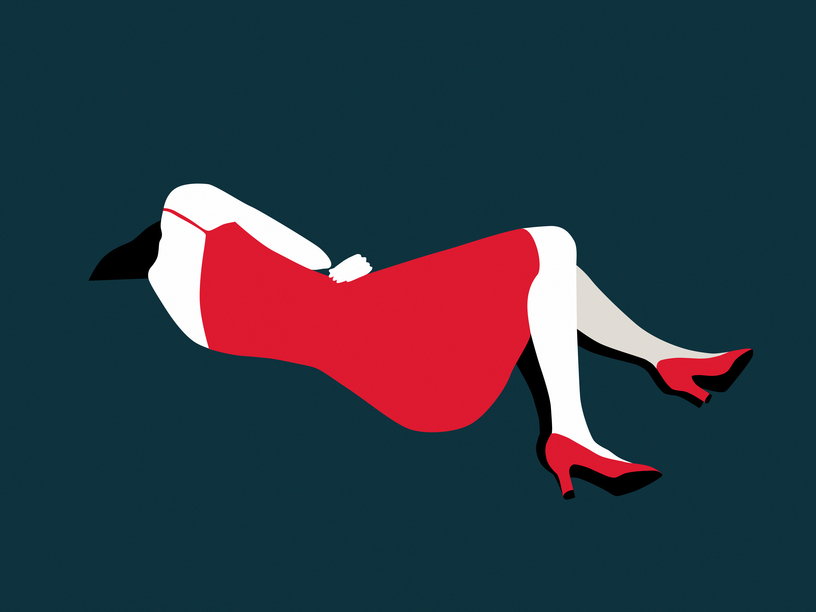

Acid attacks – a burning issue

Violence against women continues to be huge problem in India. Acid attacks is the most horrifying. Acid attacks are at an all-time high and increasing every year, with 250–300 reported incidents every year. Although acid attacks occur all over the world, this type of violence is most common in South Asia. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2516606920927247. In most cases, this crime is linked to a relationship gone sour, marriage, or dowry issues. It’s the worst form of revenge, where acid is used to disfigure women permanently, snatching away their dignity forever. These vicious attacks lead to untold physical, mental and social damage. A few days of news and sympathy are not enough to give women the strength to survive. This is summed up well in the film ‘Chhapaak (Splash) https://www.hotstar.com/ca/movies/chhapaak/1260020620, directed by Meghna Gulzar. It is a biographical drama, based on the life of an acid assault survivor, in which the survivor says, “He attacked me once, but society attacks me every day.” Stories of violence like this reminds women the world is not safe for them, discouraging many to be out in the world. Just another insidious way to keep them at home and financially dependent.

The Kanoria Foundation https://kanoriafoundation.co.in is an NGO that supports the surgeries of acid victims and collaborates with educational institutions such as universities to help with their education. It also offers financial aid for their children’s education.

Too many ways to discriminate and discredit women

Women HIV carriers find it harder to be employed. I met a woman who married the man her parents had chosen for her. The man had concealed the fact that he was HIV-positive. She discovered this when she was pregnant. She was unable to deal with this ordeal. In another case, the boy’s family claimed that their son became infected due to the girl’s HIV infection. The truth eventually came out, and the girl was exonerated. Even though this case caused a furor, Indian society will still never accept the girl if she is infected. HIV-positive women have no way of gaining financial independence.I was therefore surprised to read that a couple of non-governmental organizations in Ahmedabad are selling ‘dry food’ produced by HIV-positive women.

Divorce is yet another significant issue. Recently, it was reported that a woman committed suicide because she was being abused by her husband. She had the means to return to her parents’ house, but she was afraid to even try because she would bring them shame. Society would judge her and her parents. The truth is never revealed in these situations. Only one girl dared to post on social media that she couldn’t find the right man to marry until she was 32, and that her relatives treated her badly when she attended social functions. “Now that I am married, people have begun to invite me. I created a website called ‘Human is around you, you are not alone’ and I’m getting a lot of questions regarding our society, which is a big cause of depression”, she says.

Disabled or divorced women face further discrimination. Not to mention, in Indian society, girls do not have a right to their parents’ property.

With so much stacked against them, financial independence is a crucial part of the feminist agenda in India. Without it, women cannot rise to their full potential. Without it, women in abusive, unfulfilling marriages can never leave. Without it, they languish on the margins. Without it, their future is bleak.

Achieving financial independence safely is the Indian woman’s first step towards finding and retaining their dignity.

Related Reading

The Rupee Road to Independence: A Letter from a South Asian Sister

In India, only four out of ten women are financially independent. Dharaa Patel hopes to change that.

Dimple Mukherjee Finds Her Voice—And Founds A Business

“I didn’t learn to speak, metaphorically, until I left my parents’ home and went to university.” –Mukherjee