Imagine this: an eco-just world that enables all genders to flourish, with their basic needs met for healthy food, water, shelter, safety, agency, belonging, human touch, respect, and personal growth.

I know many others, not just activists, think such a world is possible. Increasingly, tech gurus, CEOs, startup founders, mainstream politicians, and investors have joined the choir. I am a person whose hope requires continuous feeding so I eagerly read and highlight their thought leadership articles and better-future “unity now” books. I was floored yesterday to read this article, “Unless It Changes, Capitalism Will Starve Humanity By 2050,” in Forbes Magazine, the voice of big business in the United States.

Could it be that the tide is turning this time for real, with more people on the side of tackling the dysfunctions of patriarchy and capitalism? One thing I have noticed as a measure of hard evidence is that social entrepreneurs (who operate at the intersection of philanthropy and business) are getting a warmer welcome in business incubator and accelerator programs. In the past, they were often given a pat on the head (myself included) for cuteness and a one-way ticket to the back of the local community centre, and a desk beside the toy box.

I have spent time by the toy box (and in the toy box) as a social entrepreneur for more than 15 years now, so I am encouraged by this discourse shift, which is crucial to right a world marred by climate change and war-driven human migration, mass extinctions, gross income inequalities, an unhelpful global political shift to the right—need I go on?

But the stark reality is, despite all the studies, the rise of B Corp certifications, warm welcomes, and government-sponsored social finance funds, a quick look at the facts and figures tells us that we still really have no idea how to help social entrepreneurs grow impactful, solutionary enterprises while also sustaining themselves, their families, employees, and the communities they live in. As a result, social enterprises (in Canada at least) often remain small (fewer than three people) and rely heavily on life support dribbling in from donations, odd-ball grants, and micro-finance scale investments. It’s not unusual to see celebrated social entrepreneurs holding down a traditional day job while trying to grow their company just to pay fair salaries, and themselves, for years.

Social enterprises that provide services or education versus a product have an even tougher time. It’s easier (though slightly) to find financing when you involve the purchase of hard assets like a building (Centre for Social Innovation) or pre-sell a physical product (Lucky Iron Fish). In many mainstream, mixed incubator and accelerator environments, social entrepreneurs are still not taken seriously, and routinely feel like outliers that need to go elsewhere for relevant support.

We need social entrepreneurs to succeed more than ever. So where are we going wrong?

Time to Embrace the Old—And Make It New Again

Systemic blind spots are part of the problem. Social enterprises don’t fit neatly into the for-profit or non-profit box. As a result, the majority of today’s accelerators and incubator leaders and progamming folk do not have the skills or experience required to help social entrepreneurs consider their full range of options when it comes to structuring, designing and growing their new enterprise.

One of the most glaring omissions? Our startup ecosystem’s ability to support the creation and development of co-operatives, which is one of the most successful, evidence-based ways to create a large, profitable social enterprise that serves people and the planet. Typically, programs promote just two binary options: set up as a non-profit or for-profit. Sometimes, advisors actually recommend both so you can raise money and qualify for foundation grants. For a new entrepreneur, figuring out one legal form and paying for tax filings is already daunting enough, let alone administrating two legal forms, paying for two tax filings, plus recruiting and serving two boards to boot.

Few point out that there are other ways to structure and finance a social enterprise, like, for example, creating a for-profit co-operative.

Co-operatives have been around since 1862 (corporations have been around since the 1780s). Part of the problem is that our thinking about co-operatives, the world’s original and oldest social enterprise legal form, lags far behind the times. When we hear the term we imagine small quaint farms and food co-ops, newcomer credit unions, or city housing. Yet, co-operatives all around the world—and in Canada—are thriving, growing, and solving social and environmental issues, all while not exploiting people or the planet to do so.

Today, there are more than 9,000 co-operatives in Canada and 750,000 worldwide. According to the International Co-operative Alliance, the top 300 co-operatives globally report US$2.1 trillion in revenues. In Canada, co-operatives generate $54 billion in GDP (compared to the $9.1 billion created by the Canadian tech sector) and paid $12 billion in taxes and created jobs at nearly five times the rate of the overall economy. Research shows that co-operatives are twice as likely to survive than traditional businesses, often because the governance structure provides a strong pipeline for enterprise succession. Research also shows that 76 percent of consumers are more likely to buy from co-operatives.

Interestingly, there’s a strong feminist principle embedded in the very structure of co-operatives, which requires a wide variety of stakeholders be represented at the board table.

Modern, new co-operatives are springing up in an array of surprising sectors: green energy, breweries, co-working spaces, retail, networks, wine, arts facilities, and media. Stocksy, a platform-based co-operative, and a favourite of ours (we buy a lot of photos from them) puts the power back in the hands of its 1,000-plus shareholder artists, ensuring a fair distribution of profits, encouraging collaboration, and ethical business practices.

Oh, and sex! Come As You Are claims to be the world’s only worker-owned sex shop. The online co-operative offers “sex-positive” products, advice, and workshops as well as education and outreach to the community.

The principle related to sharing the wealth may well be what inspires people working in co-operatives to do well, for co-ops can and do make large profits, such as Ocean Spray, a global enterprise that generates $2 billion a year to support its 700 farmer members, processing facilities, and 2,000 employees. Arizmendi Bakery has spawned some five sister co-ops in California.

Why Ignore Successful Models?

If co-operatives are so great at growing, creating jobs, long-term financial stability, plus wealth creation and fair wealth distribution, why don’t innovation policymakers, startup incubators, and accelerator programs encourage their creation and development?

Well, it’s simple. Co-operatives do not serve traditional investor interests, and traditional investor interests overwhelmingly dominate and drive entrepreneurship incubator and accelerator programming.

Why don’t traditional investors like co-operatives?

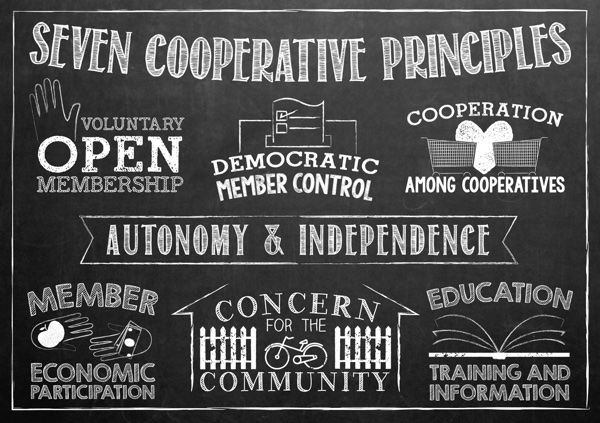

Co-operatives are bound to reinvest or distribute profits to workers and/or member-owners versus prioritizing a small preferred share-class group of outside, privileged investors. Co-operatives are also nearly impossible to sell or flip for a quick investor return—or take over management if investors are suddenly dissatisfied with the social purpose’s impact on the rate of growth. Co-operatives are virtually mission-drift-proof, meaning the social mission today won’t fly out the window tomorrow because the mission is legislatively backed. In addition, members—each with one vote, regardless of the size of the stake in the co-operative—control that mission.

Essentially, co-operatives combine the best of the for-profit and non-profit world. And they might just be what we need more of today. They are built to reverse wealth inequality—not exacerbate it. Their seven principles require members to support the health of the planet and the well-being of their communities and all people.

There is now one accelerator in the US that’s focused on helping founders start co-operatives, the Boston-based Start.Coop, a partner in the Fledge Accelerator network that includes Tech Stars, Bainbridge Institute, and Seattle’s Impact Hub. But sadly, there is no such equivalent in Canada. We know. Because we looked. And we had good reason to do so.

The Journey to Becoming Canada’s First Womxn-Led Feminist Media Co-op

At our last advisory board meeting, the LiisBeth Media team and I decided to structure LiisBeth as a multi-stakeholder co-operative to support our mission. We believe this structure will enable us to create impact, achieve financial sustainability, and enable the enterprise to flourish for a very long time—or at least as long as it takes to achieve gender equality globally. With no local government-funded incubator or accelerator program around, we are left with having to navigate the journey on our own.

To learn more about co-operatives, we joined The Canadian Community Economic Development Network (CCEDNet). It offers a wealth of information on co-operatives and referred us to several experts.

For implementation expertise, we went online to find a law firm that had experience in the co-operatives space to help us do this right. Luckily, we came across Iler Campbell LLP, a “law firm for those who want to make the world better” (it also offers affordable rates).

To help us with important details, we have enlisted several co-op experts who have experience with discerning and understanding implications of membership categories, plus how to market co-op shares, lead and govern in a transparent, inclusive way. Leading a cooperative requires sophisticated feminist forward leadership and management skills.

These are complex challenges that won’t be easy to solve but we’re excited to tackle them. In the coming months, we’ll share stories about what we learned and let you know who to go to if you, too, are interested in exploring a co-operative legal form for your social enterprise.

These resources and knowledge exist, most likely, outside of your local startup ecosystem. It’s there. You just have to find it.

Creating researched and inspirational content to support and advocate for feminist changemaking takes hundreds of hours each month. If you find value and nourishment here, please consider becoming a donor subscriber or patron at a level of your choosing. Priced between a cup of coffee or one take out salad per month.

Support LiisBeth

Related Reading

https://www.liisbeth.com/2019/09/24/a-better-way-to-be-better/