As someone who wholly embraced and participated the environmental and sustainability movement in the early 2000s (to the point of founding the World’s only Platinum LEED-certified dairy), the opportunity to hear Naomi Klein speak on the state of the environment and environmental debate in Canada on Oct. 17 at the University of Toronto was something I just couldn’t miss.

In her talk, Klein cited many troubling facts, but the most burdensome of these was that after 50 years of environmental activism and effort, as a society, we still struggle to make meaningful progress.

Even with scientific evidence and now actual lived experience of the impact of growing levels of green house gases on the planet, and even after the signing of the 2016 Paris Agreement, environmental activists like Klein remain skeptical. While 55 countries representing 38 per cent of the world’s emissions agreed to implement plans that will “limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change,” Klein argues that the targets are already at risk. Several countries continue to approve large scale industrial projects that will make this achievement mathematically impossible, she notes. Canada for example, played an important role in convincing leaders of the need for even tougher measures, yet recently approved an emissions increase of 43 per cent for the Alberta Tar Sands’ new fossil-fuel-based pipelines. In practice, this will increase Canada’s emissions well beyond the target set in Paris.

Furthermore, environmental watchdog organizations, like UL Ventures (formerly TerraChoice), an independent global science safety company, continue to call out case after case of greenwashing. The term “greenwashing” was coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld in 1986 to describe instances in which a company, government or any other group promotes green-based initiatives or images but continues to operate in ways that damage the environment. In fact, according to UL, 95 per cent of green products assessed today are guilty of greenwashing.

While we are patting ourselves on the backs for our day to day efforts, Klein suggests, we as a society are not doing nearly enough. Yes, we can change lightbulbs, buy green products, build LEED-certified buildings, and ride our bikes to work in the snow. But it turns out that in the face of continuued approval of large scale, fossil fuel based industrial projects that serve capitalist, corporate and national interests, these individual efforts represent but a few colourful grains of sand on a 150-mile beach.

The environmental movement has learned it is up against something much bigger than political will. It’s up against the reluctance of us all, and especially of those in power, to give up our 21st century way of life.

Common Ground: From Greenwashing to Gender-Washing

While listening to Klein, it occurred to me that the gender equality movement (known more commonly as feminism) is a lot like the environmental movement.

The literature in both fields indicates similar causal roots (unequal power dynamics, capitalism run amok, neoliberalism), and both are deemed exploitative in nature. They are both wicked problems that require intersectoral solutions. Each domain is full of third-party certification opportunities to help consumers separate the curds from the whey (LEEDS, Green Globes, ISO 14001, WEConnect, and Buyup Index).

Taking this idea further, many similarities can also be seen in the ways that corporations and even governments pay lip service to these two philosophies to turn a profit, or a vote.

In 2009, TerraChoice developed its list of the “Seven Sins of Greenwashing”, which became a widely-used taxonomy to categorize common types of greenwashing activities. The seven sins are: Hidden Trade-off, No Proof, Vagueness, Worshiping False Labels, Irrelevance, Lesser of Two Evils and Fibbing. Categorizing practices like this helped consumers to recognize and understand different types of greenwashing activities so they could make more informed choices.

The seven sins list was indeed useful during my days as a sustainable enterprise entrepreneur. And so, I thought it might be similarly helpful to develop a “Seven Sins of Gender-Washing” list to help us all better identify gender-washing practices. The term “gender-washing” describes organizations that try to sell themselves as progressive on the gender equity front, when in reality, they are not.

Here goes.

- The Sin of Re-Skinning – A company that attempts to “look” like its work environment is currently gender progressive by ensuring its company website, annual report, and advertising copy has lots of women in the photos. It uses positive gender speak in its corporate communications, and content marketing output, yet when you check out the gender composition at the top it is 80 per cent, or worse, 100 per cent men.

- The Sin of Worshipping False Progress – Where corporations create special “We Love Women Who Work Here” days; buy tickets to women empowerment lunches for female staff; appropriate initiatives like the UN’s “HeforShe” campaign for commercial gain; or give to Oxfam’s “I Am A Feminist” campaign as part of a marketing campaign, yet internal organizational policies and day-to-day gender-biased cultural practices remain fundamentally unchanged.

- The Sin of Distraction – A claim suggesting the company is pro-gender equity, but upon digging deeper, you find the claim is based on a narrowly defined initiative without concern for the larger, more important issues. For example, in 2011, Walmart trumpeted its new Global Women’s Economic Empowerment Initiative, which involved a commitment to source $20B from women-owned businesses. Sounds good, however, this amounts to just 5 per cent of its overall expenditures. And, Walmart was already buying from some women-owned firms. The initiative came on the heels of a class action suit launched against Walmart by its 1.5 million female associates for its allegedly discriminatory practices.

- The Sin of Corporate Inconsistency – Where distant head offices write, implement and impose gender equity and inclusion policies, and promote this as progress, but their branch plant or satellite operations in other jurisdictions don’t follow suit and are not help accountable for doing so.

- The Sin of Positioning Basic Compliance as Leadership – Companies that tout government-mandated policies—like pay equity or parental leave—as gender-progressive initiatives; or Ontario organizations that send out press releases announcing they “have done away with dress codes” (meanwhile dress codes have already been deemed unacceptable by the Ontario Human Rights Commission in 2016).

- The Sin of Irrelevance – A case where a company promotes the fact that 65 per cent of its employees are women, however they are all on the factory floor, are mostly hired as part-time workers with no benefits, and have no representation in senior management let alone on the board.

- The Sin of Only Counting Heads – A case where a company trumpets the addition of two new female board members or the promotion of a female manager to VP to change the ratio, not the culture. Sometimes, “non-trouble makers” or like-minded women who won’t challenge the status quo are chosen by design. This does nothing to change the culture or support inclusion. Appointees we hope to see serve as changemakers become mere headstones at the board table, and their ability to create change for all genders in the company is amputated-usually at the voice.

When it comes to the seven sin taxonomy, many may argue that perhaps these initiatives are not really sinful at all, but demonstrations of positive intent. The phrase, “Let’s not make the perfect be the enemy of the good,” comes to mind. As a colleague of mine said, “At least they changed the pictures on the website—it’s a start isn’t it?”

Once again, we can learn from our environmental movement counterparts. Yes, some organizations, keen to be perceived as market leaders in the gender equity space, might put the cart before the horse—a “fake it till you make it” approach—advertising where they want to be, and not where they are today. Sorry, but that still makes it gender-washing-until their policies and results catch up with their claims.

Do Organizations That Gender Wash Eventually Improve Authentically?

Furthermore, evidence from the green space shows that few companies ever actually move (willingly) beyond their greenwash-oriented status. Why? Turns out “the perfect” is not the enemy, it’s the business case decision-making framework.

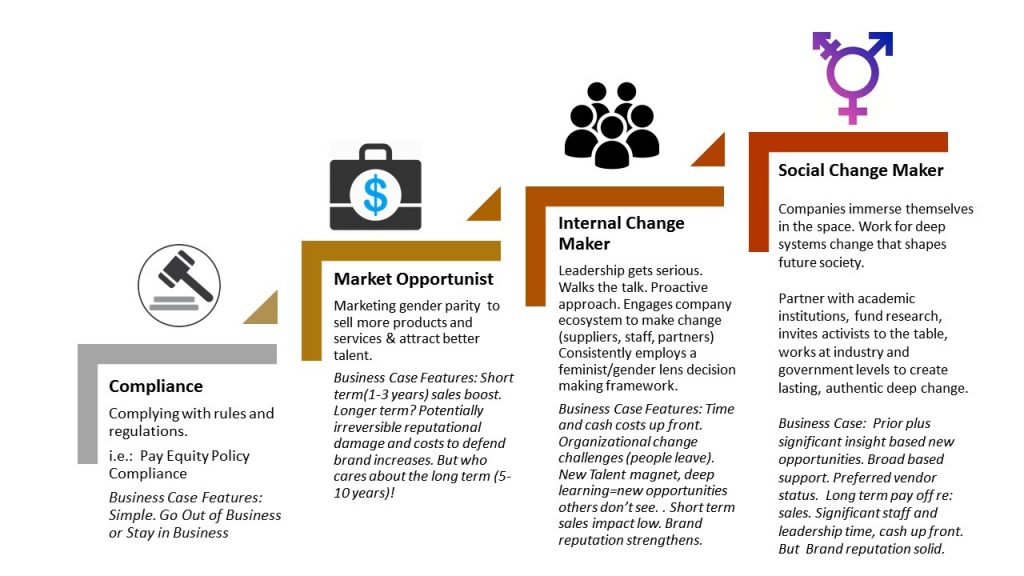

To help organizations understand what being stuck in the short-term business case loop looks like, the sustainability field developed something called “The Maturity Curve”. Different consulting firms have customized different versions, but the core idea is the same. Becoming a truly environmentally positive enterprise is a journey. Points along the curve articulate the pros and cons from one state to another. It can help decision makers see that some returns take a long time to be realized.

If we apply the maturity curve concept to the gender equity space, it would look something like this:

As the chart illustrates, the reason companies in the environmental space actually never move past the compliance or market opportunity levels is because short-term returns are possible at those levels. Consumers eager to vote green with their dollars buy the products based on the ads, the green coloured package and superficial claims. Both believe they have done their bit.

Organizations that do want to make a substantive difference need to move up the curve. However, as you move up the curve, so do costs, and returns take more time to realize. Maturing takes investment. As we know, not all quarterly-earnings-oriented organizations can stomach a long return horizon. As a result, only a small percentage of organizations make the leap to the next stage of commitment.

This also speaks to the fact that that there is a limit to what we can truly expect from large corporations and institutions when it comes to changing the world. Few will ever, if at all, reach the fourth stage, unless these goals were part of the founding vision in the first place.

From Gender Washing to Gender Equity, to Action

So what does our understanding of green washing and role of companies in helping to drive environmental change tell us about the pace and nature of change we can expect in the gender equity space?

For starters, we can remind ourselves that real, deep social change happens at a glacial pace and is inherently complex. It involves changing institutions, culture, underlying, interlocking systems like capitalism and culture, versus just the products we buy or companies we work for.

We can also learn that individual efforts, such as “buying your way” out of a significant and fundamental social problem, make us feel good, but don’t do nearly enough. We must move from being consumers to becoming citizens again. As citizens, we can and should re-engage at political levels, read, think critically, stand up (on the street if need be, not just while sitting on your couch using Twitter), speak our truths, get uncomfortable, and take the time out of our days to contribute meaningfully to an intentional larger movement.

As Klein said two weeks ago, to really make a difference on these kinds of problems, we need an intersectional collective, activist effort.

In her view, just as the colonialists saw their colonies and their natural resources as their own larder for growing their personal stature and fortunes at home, society has for too long viewed women as an inexpensive resource to exploit. Women have been used as “spare parts to fill in, versus lead[ers in] our economy.”

In short, we need to end our dependence on the extractive economy to save the planet, and similarly end our exploitation of women to advance society. And we need active, engaged and informed citizens, not consumers, to get there.

Now that would truly change everything.

Related Readings and Articles:

“Entrepreneurs by Choice; Activists by Necessity” by Cynthia MacDonald