During a recent Sunday evening at a school gym in Toronto, the Ninja Monkeys, a co-ed floor hockey team comprised of five women and seven men who have played together for nearly a decade, nailed their competition to the wall. Then they headed to a nearby bar to celebrate their 13–9 win with a round of drinks.

Team captain Tammy Symes, a 39-year-old recreational athlete, loves to play sports so much she signs up for two softball teams and two floor hockey teams each year, sometimes adding in ultimate frisbee or soccer for an extra dose of fun. “I’ve made so many friends, it’s unbelievable,” said Symes. She also gets to flex her leadership skills, serving as captain for most of the teams she plays on.

Supporting all that healthy fun and personal growth is a unique business model. Kristi Herold founded the Toronto Sport & Social Club in 1996. She had competed on rowing and ski teams at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., but when she graduated and moved to Toronto, she fell into an accessibility gap in recreational sports—especially for women.

“I thought maybe I could play soccer. But at the time, the only soccer I could find for women was highly competitive,” said Herold during a recent interview at the company’s Toronto office. “I couldn’t play at that level.” Yet she also couldn’t imagine her post-university life without sports. “If you go and play after work, you’re going home happier, you get a little sweaty, you’ve had some laughs on the field. You’re going to be less stressed, and your health is going to be better.”

Herold, who ran two small businesses while completing her commerce degree, seized on the gap in recreational sport for adults as an opportunity to launch her own company. “I realized I had to go out and do something on my own,” said Herold, who sports an athletic build, wild curls, and a ready smile. “I’d heard about these clubs in the US and I thought, well, I’ll give it a try.”

That was back in the analogue days, so Herold called up friends and friends of friends to see if they might be interested in playing on a co-ed sports team in a downtown location. She explained her idea as “intramurals for people who aren’t in university anymore.” By targeting recent graduates who faced the same lack of sporting options she encountered, Herold managed to sign up 52 co-ed teams that first season to play soccer, ultimate frisbee, flag football, basketball, and beach volleyball.

She charged $350 per team for the season, signed Spalding and Wilson as equipment sponsors, and launched a sporting enterprise that, 23 years later, has 130,000 annual participants playing about 30 sports. It employs some 50 full-time and 250 part-time staff, has expanded to eight Canadian cities, and can boast of being one of the largest sports and social clubs in North America.

Even in her first year running the future sports empire, Herold knew she was on to a good thing. “I was out at games every night…and showing up at sponsor bars afterward to make sure everyone had a good time.”

The concept is relatively simple. Players pay to play for a season that runs about 12 weeks. They can join either as an individual or a group can sign up as a team. Sport & Social Club handles all the organizing: matching individuals with a team, providing equipment, setting rules, creating a schedule, renting venues, tracking standings, and arranging social gatherings.

There are single-sex, co-ed and open leagues. The goal is to make it welcoming to anyone, regardless of skill or experience, with an emphasis on fun and making friends. On co-ed teams, there must be a minimum number of both men and women in play at all times. As Symes said, “If you join, you get played, and you have a good time.”

Said Herold: “I wanted to show it was possible to start something that everyone can play.”

When her business proved to have legs that first year, she formed a 50/50 partnership with her boyfriend, Rolston Miller. He had recently retired as a semi-pro cyclist and was looking for flexible work. As the company had no money for stamps, his first task was to deliver printed flyers that promoted seasonal registration. He did that, of course, by bike.

The two married later that year. Miller focused on building a digital platform for the company that would eventually become the foundation for internal and external communications. Herold led the business as CEO. “We were really hustling,” said Herold. “We grew by word of mouth, didn’t spend much on marketing.”

One of the club’s earliest hires was Rob Davies, an operations whiz. In 2007, Herold and Miller invited Davies to buy into the company, which is now run by the three partners, with Herold as CEO, Davies as president, and Miller as director of marketing.

Meanwhile, on the home front, Herold and Miller were struggling to manage a growing family with three young children. They found ways to distribute the workload at home according to practicality, rather than gender expectations. Still, Herold often felt overwhelmed. She’d grown up in Sudbury; her father was an entrepreneur and her mother stayed at home. “I grew up wanting to be both of them, which was challenging,” said Herold. “I felt I was failing, both as an entrepreneur and a parent.”

That crisis led Herold to take bold action. In 2005, she decided to step away from the business for 16 weeks of the year. She did that for several years. It wasn’t easy, but it seemed possible, Herold said, because of her innate leadership style, which she described as “bottom up.”

“I like to think of me as the base of a tree. I’m here to support. I say, tell me what I can do so you can go and do your work. It’s not me, standing on top, talking down.”

She and Miller divorced in 2012 but they’ve maintained their business relationship.

Now, after a decade of focusing on family while Herold placed the business in a slow-growth mode, she’s back in her CEO chair full-time. And she has a new goal of getting one million people off the couch, which means leading the company into an era of ambitious expansion.

Over the past two years, Sport & Social Group has expanded into new markets by buying up clubs that were already operating in Ontario and Michigan. Leaning on the parent company’s infrastructure and its custom digital platform, the newly acquired clubs can sign up and retain more members than they had previously. More acquisitions are in the works.

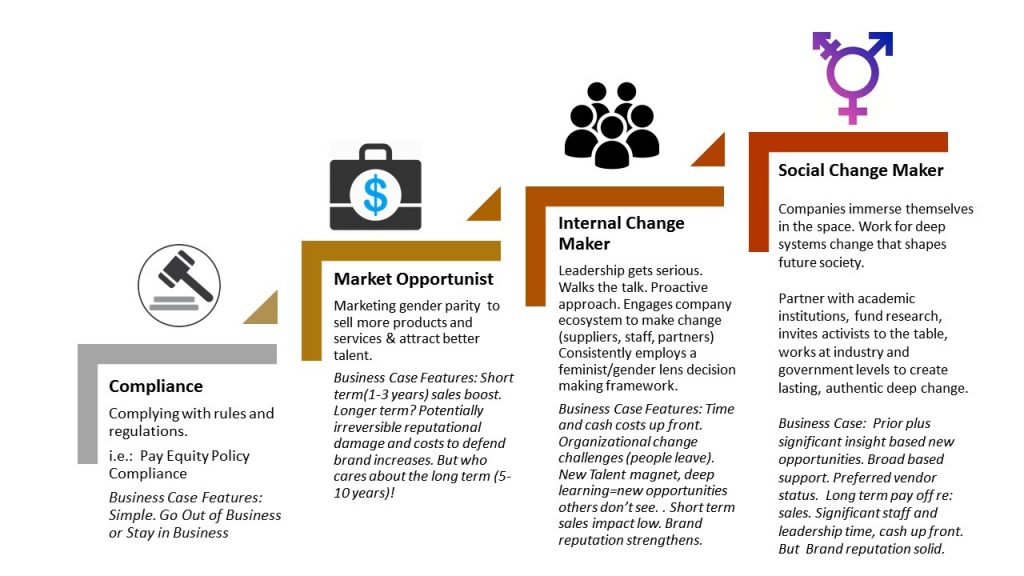

In the #MeToo era, ambitious growth in the sport industry comes with a responsibility to create a safe place for women. Herold aims to create gender balance—in the workplace and at play. Currently, about 40 percent of the club’s staff is female. And about 45 percent of its membership is female. Herold celebrates those stats in the male-dominated sporting industry.

So far, the company has not faced harassment issues, but Herold wanted to be ahead of the issue and hired an old friend from Queen’s University, Bay Ryley, to deliver online training for employees, teaching them how to identify and report harassment.

Sport & Social Group’s also developed gender policies that are trans-inclusive. Such measures are particularly important in co-ed sport, with teams required to have a minimum number of both genders in play at all times. For example, on the soccer field, two of six players must be women and two must be men. The other two can be any gender.

To register in single-sex or co-ed leagues, players can self-identify as either male or female at registration. Those who don’t identify a gender when they register are welcome to play, though their teams may not count them as either men or women to meet gender requirements. In open leagues, there are no gender requirements.

Within Herold’s expansion plans is a mission to improve access to sport for children. The company has started a foundation called Keep Playing Kids and aims to connect adult mentors—including Sport & Social members—with kids who need sport support. “We know that if you play when you’re younger, you develop a love for it, and you’re more likely to play as an adult,” says Herold. “We want everyone to keep playing.”

LiisBeth depends on reader support to stay ad free and independent! But we can’t do it without your support. Please consider a donation today!

[direct-stripe value=”ds1562329655623″]

This post was made possible due to the generosity of Startup Toronto.

Related Article

https://www.liisbeth.com/2017/01/18/how-to-be-a-bold-betty/