When audiences were made aware of the news of Bell Media’s sudden firing of CTV News anchor Lisa LaFlamme at the end of June, Canadians erupted with collective outrage. Whether, as speculated, her dismissal was the result of ageism and sexism or whether it was a clash of newsroom personalities, Bell’s tepid excuse that it was a “business decision”—a corporate-speak version of a patronizing pat on the head—found little traction. The giant communications conglomerate’s arrogant expectation that “60 years of trust” would eventually override the public’s memory hangs in serious doubt. LaFlamme was one of Canada’s most beloved and—more importantly—most trusted anchors.

The issue roiling beneath the anger at Ms. LaFlamme’s dismissal isn’t going away: it isn’t specifically an issue of sexism or ageism, or an issue of race (LaFlamme is a white woman who has been willing to age publicly; Omar Sachedina, her replacement, is a man of colour), although each of these facets of the problem is quite enough on its own.

The crux of the matter is the conflict between what is good for news (and audiences) and what is good for business.

Who Does Modern Media Really Work For?

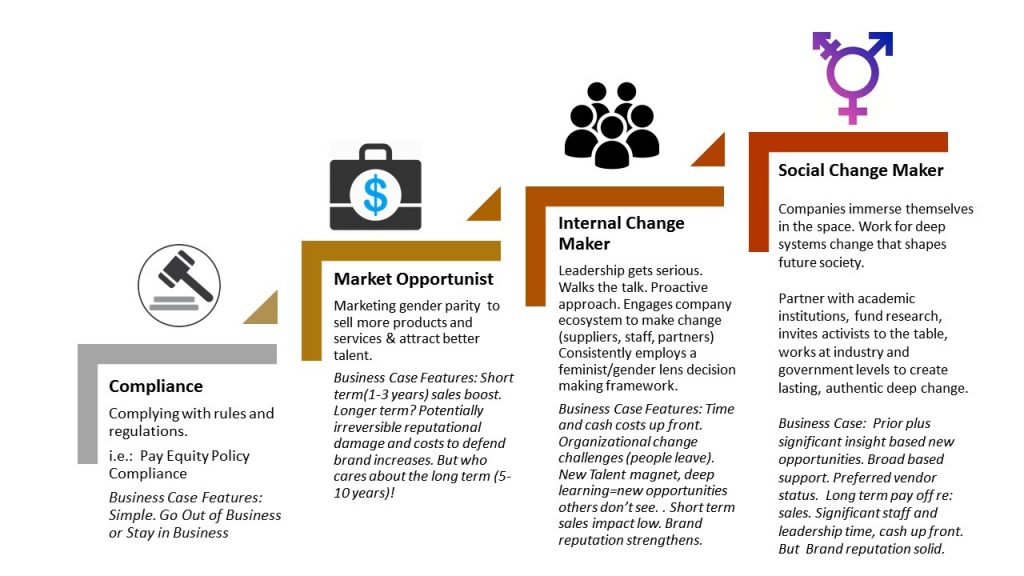

What is good for business—traditional business, that is—is anything that will produce profit. The greater the profit, the greater the success. But throughout the pandemic we have become increasingly aware that this approach has its price. While some reap the benefits, more face lives of greater insecurity. But how can we track the success or failure of this system if the very ways by which we share information no longer report on it? It’s not until the cracks start to show, until the harm the system causes is too great to be ignored—too many people of colour shot by police, too many immigrant workers dying due to substandard living conditions and inadequate pay, too many people losing their homes due to a lack of affordable housing—that we question the information we have because it doesn’t match the world we live in anymore. Celebrities, sex scandals, and outrage garner clicks that increase profits. The slow swell of inequity and destabilization is more newsworthy, but unless it can be blamed on a scapegoat, it is not lucrative.

We have watched with growing anxiety the rise of Fox News, the proliferation of clickbait headlines, and the erosion of our core institutions (media, academy, government) as “business” decisions have disrupted their function and challenged our confidence in them.

The fourth estate, our press in Western democratic nations, was conceived as a place of checks and balances for power, which includes systems of power as much as actors within that system. Our business culture is driven by a pursuit of power that is linked to money. The commodification—the Foxification, even—of public information has resulted in a media system where checks and balances are compromised. News media cannot remain accountable to the public good through transparent and unflinchingly ethical information production AND be accountable to the interests of advertisers and corporate owners—at least not sustainably. Information can be entertaining, and its dissemination can even support business, but in order to function as intended, the news media must be free to ask any question, unconstrained by consequences to the interests of the parent company/owner/powers that be.

Video clip from “Network” (1976) during which the Network CEO explains the true relationship between big business and media to TV anchorman, Howard Beale played by actor Peter Finch.

People in the media have known about these issues for a very long time. The black comedy Network spoke to the problem in 1976. Following the mass purchases of media outlets in Britain, Australia and the US by Robert Maxwell and Rupert Murdoch in the late 20th century, the news satire Drop the Dead Donkey was born in 1990. The concerns these programs aired (and they are extensive) were then more than validated by criminal violations by both magnates, most notably by Murdoch, with his wire tapping scandal, and then reports of rampant sexual harassment at his wildly financially successful media outlets. However, the warnings have continued to go unheeded. The result is that today we have a fragmented information production system distrusted by an increasingly polarized public sphere, creating an information miasma from which we have not yet begun to emerge.

The answer to this fracture is a system of information production that people feel they can trust—one that produces stories that share facts and information, question norms, and help us face our problems so that we can solve them before they hurt us. Ethically produced information is not only accountable to ethical standards set for journalism, but it seeks to find ways of telling stories that reduce bias and increase accountability, not only to readers but to the people being written about and to the ways in which we make the information in the first place. Ethical outlets challenge implicit bias in their newsrooms, in the management of their teams, and in the structure of the stories they tell. Ethical information production asks us to break down the things that we take for granted before they do damage—overreporting of minority crime, the subtle shifts of language that betray double standards, the long-held unspoken assumptions that prove, on examination, to be completely wrong. But to accomplish this, ethical media has to be able to challenge the very system that validates “success” or “failure”, the dominant system of power. Which is precisely the object lesson we have witnessed with Bell Canada’s approach to firing Ms. Laflamme. Their inept response speaks to their conviction that they don’t have to tell the story we are demanding to hear. And THAT is what makes it so hard for Canadians to swallow—the knowledge that Bell is not replacing trusted storytelling with more trustworthy storytelling. It is already replacing it with more spin.

Through wars, intense polarization of the political sphere in Canada, and pieces on gross inequities in our communities here and abroad, Ms. LaFlamme gained the respect of diverse audiences. As one of Canada’s many “hyphenates” (Canadian-nameyourcountry), and, more importantly, a hyphenate of a country that at one point was vilified by Canadian media during one of the many conflicts we’ve watched in the last 40 years, I, like many Canadians, have grown very cynical and very selective of the news reporters I will listen to. It was while Ms. LaFlamme was interviewing someone on the conflict in Iraq that I realized that her questions allowed for more nuanced understandings of conflict and of the contextual realities of those simply identified as “evil” or “bad” or “other” on other networks. And when she spoke of the conflict in my father’s homeland, the way she spoke of the country and the people shared their lived experience of the conflict they had been involved in. She was still reporting the news, and with it the actions the people involved could not and should not hide from, but she was also able to relay the stories without seeming to paint the people “evil” with a single broad stroke. She was able to speak to bad things being done, sometimes, by good people.

This is the news that we all need—the news that allows us to look at what it means to be human and to do things that might not be right, or seen as right, by others. To open conversation is to allow for understanding. Judgment and vilification create conflict and close off opportunities for dialogue, contact, and peaceful solutions. This empathy was the real gift of Ms. Laflamme’s reportage. And because of this unique ability of hers to convey the complexity of human experience, audiences from diverse groups in Canada were willing to use what she had to say as a foundation for discussion. That is the best that we can hope for from news. And because of this, she was, at the end of her time at CTV, the anchor of the highest-rated news program in Canada.

Ratings aside, Canadians describe her and her work as being marked by journalistic integrity; she’s been called “fantastic” and a “journalism hero”. Yes, she’s won awards and has been graced with the Order of Canada, but what matters is the fact that Canadians chose to tune into CTV to hear Ms. LaFlamme speak about the world so that we could better understand our place in it. Bell’s oafish and disrespectful mishandling of Ms. LaFlamme is, in short, a mishandling of our trust and our support as viewers.

It is, of course, possible, even likely, that Mr. Sachedina will also produce stories of this quality and level of care. I won’t know because I, like many Canadians, no longer trust the way the stories are made at Bell Media: The commitment to ethics over business values, which is needed in order to tell stories that we as Canadians can build community on, has been shown to be grossly absent.

Which brings us back to the problem Ms. LaFlamme’s dismissal underlines. What is the meaning of Lisa Laflamme in this tumult? Is she merely a former employee of Bell Media? Or is she a public figure, a trusted voice of Canadians understanding Canada, who stands apart from business interests? Her work should stand above the needs of the businesses that pay for Canadian communication infrastructure. The anxiety and anger at her dismissal has been born of the fear that the Canadian public is losing a baseline by which to understand ourselves in a collective context.

When do we acknowledge that the fourth estate is crumbling because of a values takeover? Or that this same takeover may be endemic to all of our institutions? The issue is not with business per se but with the fact that business values have infused themselves in all of our institutions, even those that are not best served by them.

How To Take Back Media

To get out of this mess, we need to create a conversation led by people – thinkers, researchers, writers, journalists – we can trust. We need media that is made by people who look different and have values and expectations of the world other than those of the dominant culture. We need media made with empathy and respect for the experiences and choices of others —that is committed to investigating itself as much as the world around it, created by people who have been trained to challenge their own ideas of themselves and the way they see their world. Can this kind of media make the same kind of profits as a National Enquirer or a Daily Mirror, or the clickbait stories that have come to replace them as “popular” news? Absolutely not. Ethically produced stories are more labour intensive to make, and they are not pitched to attract sales, but to create thought and consideration of the world we live in. They require more hands and more voices to be made, and they require that those hands and voices be paid respectfully for their work. But what they produce is an information landscape that we can rely on to create the kinds of conversations that create greater security and respect for one another—the kinds of stories Ms. LaFlamme was trying to tell.

How can we do this when the cost of launching a media source REQUIRES accountability to a system whose interests conflict with the demands of ethical information production?

There is a solution. It’s not perfect. It’s small. It lacks the audience breadth and access that Ms. LaFlamme achieved. But it’s here, a tiny heartbeat fighting to grow. Independent news agencies such as LiisBeth, The Narwhal, The Greenline, rabble.ca, and yes, full disclosure, my own publication Peeps, among many others all fight to get readers information that does NOT place business accountabilities first. Rather, they place sound, reliable, well-researched, and nonpartisan (in most cases) information production at the centre of their daily work. Among these publications, you’ll find that many of them (all those listed in this publication) were started by women, notably many of whom are women of colour. It should be no surprise that those who receive the least representation in media are looking to create space for our voices. But what women founders of new media outlets lack most is policy support, access to capital, plus marketing and exposure that generates large audiences which, in turn, bring fresh ideas and emerging female journalists into the centre of the Canadian conversation. What these pioneers also need is an audience that is willing to look for us rather than have us served to them by Apple News or commercial broadcasters: an audience willing to invest in the development of this work and the ways we make it.

The most distressing lesson we take from Ms. LaFlamme’s dismissal is that even when we do get the audience, depending on the whims of telecom giants, it might not be ours to keep no matter how many people want to hear what we have to say.

Publisher’s Note: Please consider defunding profit first corporate news media outlets by shifting your subscriber dollars to indie outlets. You can find a partial but long list of outlets here.

Related Reading

News So White It’s Blinding

Lack of diversity in media is bad for democracy, business, and justice. And readers. But what’s the solution?

THE END OF FEMINIST MEDIA?

Is feminist media–or all media for that matter, dead?

Will Next Generation News Media Ownership Be Gender Balanced?

The new $645M Canadian government news media fund mostly bails out crumbling traditional media and fails to advance diversity. Despite facts that start up companies rushing in to fill the gap are largely founded by men–and white people. Is this going to help us build a more inclusive democracy?