It was meant to be a night out of fun dining with the ladies to celebrate Eden Hagos’ 25th birthday. But when she and her friends were ignored and disrespected at a local restaurant, Hagos, a longtime foodie, began to think about how the food industry treats Black people, and how Black-owned restaurants are regarded. And that eventually led her to launch Black Foodie, a blog spotlighting “the best of African, Caribbean and Southern cuisine and foodie experiences” through a Black lens.

On her 26th birthday, Hagos wrote about the incident that inspired Black Foodie’s creation — the blog post went viral. But the degree of online hate it generated shocked her – derogatory comments about her race, gender, looks. “People are telling me, oh Black people don’t tip, Black people are bad customers, they don’t deserve good service,” recalls Hagos. “They proved exactly why we need this community – living proof that I could screenshot. It’s not even like you could try to say, ‘Oh, this is what you perceived.’ It’s real, and it’s literal, and you can feel that hate.”

For Hagos, the hate not only solidified her belief in the need for Black Foodie but strengthened her resolve to make it successful. In just over a year, she has built up 11,000 followers on Instagram, attracting readers from across Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and several countries in Africa. Initially investing her own funds – the low-cost is part of the reason why she started with a website – she has since secured a couple of small business grants, including $1,500 from the School of Social Entrepreneurs Ontario’s Hook It Up program. She expanded from a website featuring recipes and restaurant reviews to a multi-pronged company that sells merchandise, offers brand and social media services to restaurants and hosts foodie meet-ups and events to generate revenue. In the future, once she’s grown her audience, she aims to sell advertising.

Black Foodie’s signature event, Injera and Chill – a play off the popular saying ‘Netflix and Chill’ – celebrates the classic Ethiopian bread injera that Hagos ate growing up. She started it in the fall of 2015 as a pop-up event in Toronto and drew about 50 people, predominantly Millennial Black foodies, to learn about and enjoy a traditional Ethiopian meal and coffee ceremony. Hagos then took the event on the road, organizing meet-ups for fans of Black Foodie in London, England and Atlanta, Georgia. Back in Toronto, she stepped up the summer 2016 event, expanding the celebration of food to a showcase of East African culture with a DJ, entrepreneurs showing their products and filmmaker Messay Getahun premiering the trailer for his movie, An Ethiopian Love. She charged $35 a ticket, and it attracted 150 guests.

Hagos, who was born in Windsor, Ont., credits her love for food to her parents, who immigrated to Canada from Eritrea, then a part of Ethiopia. Her father owned one of the first Ethiopian restaurants in Windsor. When she was growing up, she remembers him often cooking, which is significant, she explains, since in many Ethiopian households men don’t cook. Her parents knew the struggles of entrepreneurship firsthand and, like many immigrant parents stressed the importance of education. She attended both Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan and York University in Toronto, graduating with a degree in sociology. She had planned on going to grad school in the U.S. but when she didn’t have the money or see a career path that appealed to her, her desire for “freedom” pulled her toward entrepreneurship.

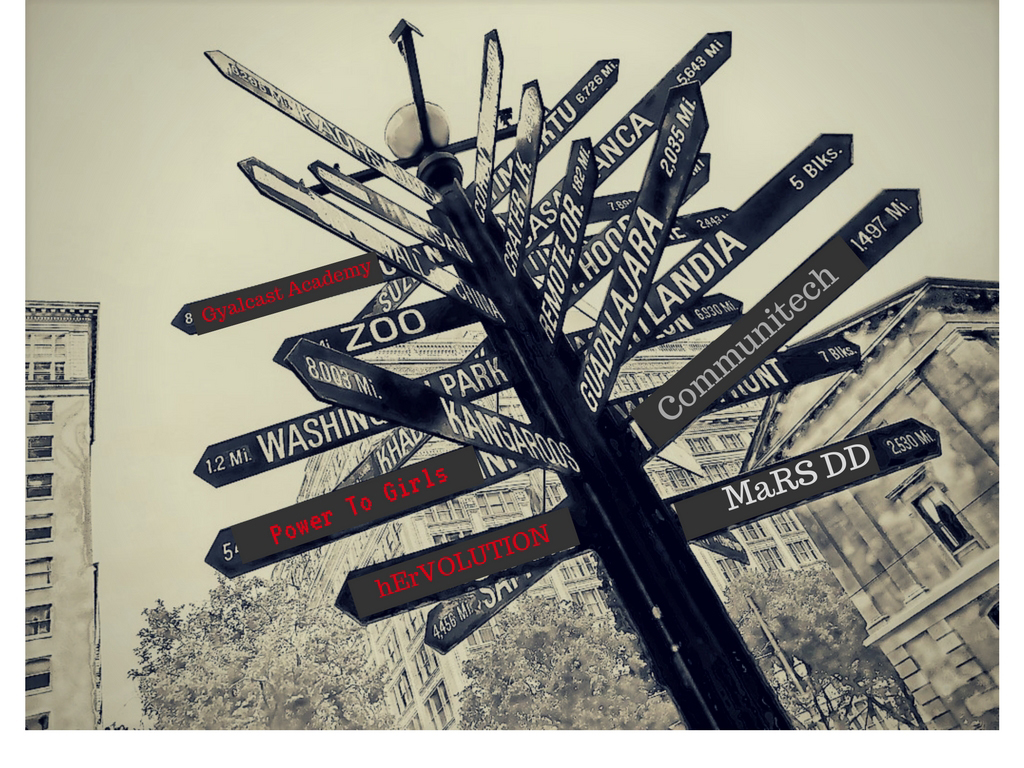

She applied for and won a spot in Studio Y, an eight-month fellowship program for innovative thinkers run out of one of Toronto’s leading entrepreneurial spaces, MaRS Discovery District. She says her thinking around education and diversity helped get her in the door. What she appreciated most about Studio Y was the opportunity to earn a stipend while developing and testing ideas. Early on, she considered creating a line of Ethiopian spices; by the time she left, she was on the verge of launching Black Foodie.

“I was encouraged by many of the staff and other fellows to dream big – nothing seemed out of grasp to that group and it was very inspiring to be in a community that valued this,” says Hagos. That said, she was often left thinking, “There are so many other people like me, why aren’t we in here?” She yearned to see more people of diverse backgrounds, as well as more conversations around her entrepreneurial mission to target her own demographic, solve problems within her community and be successful at it.

In the summer of 2015, Hagos attended a pitch competition for Black tech entrepreneurs in New Orleans, Louisiana, connected to the Essence music festival. Being in a room full of powerful, Black investors proved inspiring. Though she wasn’t ready to pitch her company then, the event made her see that the start-up world was not just for white men. She also realized that for her company to grow, she had to think beyond the borders of Toronto and even Canada. She sees more opportunities for Black-owned businesses catering to Black people to thrive abroad. Sheer numbers for one: In the U.S., for example, there are more than 37,000,000 Black people as of 2010 Census stats; Canada has just a fraction of that.

She also sees opportunity in Black Foodie’s appeal to women. Some 70 per cent of her readership – as well as the vast majority of her contributors – are women who identify as belonging to the African diaspora. “It’s crazy to me because we’re the ones cooking. But when you see the ones who are celebrated, it’s usually men. In the Black food world, it’s usually men who are hosting these events.” She also points out that popular images of Black women and food are often associated with racist depictions rooted in an African American context, such as the nanny. “I’m a Black woman, so, of course, I’m drawn to stories of people who I can relate to and I think they’re also drawn to me.”

Indeed, special events coordinator Eden Zeweldi agreed to work with the company, without even knowing how much she’d be paid. She has since planned five events in collaboration with Hagos. “[Eden’s] passion and her excitement for it gave me so much energy,” Zeweldi says. “I could actually be part of a movement that would bring food that my mother makes into the limelight.” Food stylist and photographer If Ogbue also saw the opportunity to work on Black Foodie as “a breath of fresh air.” She sees huge potential in the Black Foodie brand and envisions it evolving into a web series or television show in the future.

That’s exactly where Hagos hopes Black Foodie will be in five years. She would like to develop several Black Foodie branded shows; spearhead a huge Black Foodie festival that brings together chefs, food writers and foodies; and publish a cookbook, perhaps the first of many. Still, Hagos is careful not to get ahead of herself. The key now is that Black Foodie is sparking an important conversation, both outside and within Black communities. “My goal is not just to teach other people that we exist,” she says. “I’m interested in encouraging this conversation to happen amongst each other. Some of the things we talk about in food, you can only understand if you’re a person of colour. It’s kind of like an inside joke, and I don’t always want to be trying to explain that inside joke to other people.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

One of Eden’s favourite things to make around the holidays is sweet potato pie. Here’s her recipe. Give it a try.

Sweet Potato Pie

Filling

- 1/3 cup of brown sugar

- 2/3 cup of condensed sweet milk

- 1/2 cup milk

- 2 eggs

- 1 1/2 stick butter

- 2 large spoons cinnamon

- 1 spoon Vanilla extract

- 1 tsp of lemon juice

- 2 large spoonfuls of cinnamon

- 1/2 spoon ginger

- 1/2 spoon allspice

- 1/2 spoon nutmeg

- 2 large sweet potatoes

- Brown sugar paste:

- 8 Spoons brown sugar

- 4 spoons Butter

- 2 Unbaked pie shells

Brown Sugar Paste

- Mix brown sugar and butter together to form a thick paste

- Spread half of the paste onto unbaked pie shell and bake for ten mins or until it forms a caramelized layer (don’t let the shell get brown)

- Let it pie shell cool as the filling is prepared

Filling

- Bake sweet potatoes (or boil) until they become very tender

- Peel the sweet potatoes and cut into small pieces

- In a bowl blend the sweet potatoes, milk and condensed milk

- Add all of the remaining ingredients sweet potato mixture and blend until it has a creamy consistency then place the half the filling into pie shell and bake for 40 mins on 350.

This recipe will make two pies. Or you can use the remaining filling to prepare a sweet potato casserole, topping the mix with marshmallows and baking for the same amount of time.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Related Articles:

https://www.liisbeth.com/2016/11/08/not-incubators-entrepreneur/