Last week, while wrestling with a sense of feeling lost at sea, I picked a notebook from a shelf above my desk—at random—and began to absentmindedly flip through it. I stopped at a page where I had written down, in big bold letters, “How not to be a bitch to the system.” It, obviously caught my attention. But why did I write that? Where was I? Who said it?

I thumbed through the next few pages, looking for answers.

The next 15 or so pages were scribbled notes, ideas and quotes I had made while attending no less than five feminist events over the ten precious days before the pandemic lockdown, March 4 to March 14.

Wow. How times have changed. And so has the way I attend to my personal liberation and professional publishing work.

I suddenly felt nostalgic. But why? Now there are an infinite number and variety of online feminist events I can attend – anywhere, anytime – and all from home, at a much lower cost in dollars and time.

I came to a page marked 03/07/2020. A Saturday.

I had showed up early that morning to take in and write about the Feminist Art Conference festival at the Ontario College of Art and Design University. This was my third time attending. There was a coffee stain on the page. It triggered my memory which in a flash, reconstructed scenes from the day. I purchased a coffee from a feminist barista entrepreneur wearing a beret; she told me about her activist work while she poured. We exchanged cards. Once in the lecture hall, found an empty seat in the second row for the plenary. I rummaged in my bag for a pen and this notebook, and a few minutes later splattered some my still steaming coffee on the page as I bumped elbows with the person I sat next to. Immersed in the scene, I noticed how the room was animated with people moving about in full bodied ways. The crowd’s mish mash of hats, scarves, gloves, coats, bags, everyone squished together, arm to arm, shoulder to shoulder looked like a quilt of moving colour. You could tell by the clothing it was early spring.

Will we ever experience being together like this again?

At “gathering time,” the electrifying music muted as MC Justine Abigail Yu took the stage. I had read about her work as a diversity advocate and publisher of Living Hyphen, a magazine and community that explores the experiences of hyphenated Canadians. With a rally-cry voice, she looked out at the audience and said assertively, “Good morning! Are you ready to smash the patriarchy?”

Affirmed by the “WOOT WOOTs, Yu asked. “Are you ready to decolonize? Are you ready to end capitalism?”

We shouted back “Yes,” louder with each sentence, signaling “We are fully present.”

The rally cry culminated in disorderly applause. I remember how it felt, how subversive to shout such things in solidarity with a diverse crowd. These spaces inspire me: grassroots, feminist, places where we can safely talk about how to end capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy without having to explain or justify why we need to. These spaces are sacred. And far too few in number.

As the clapping died down, Yu said “I think this is probably the only place I can say that and get applause.”

I flipped the page.

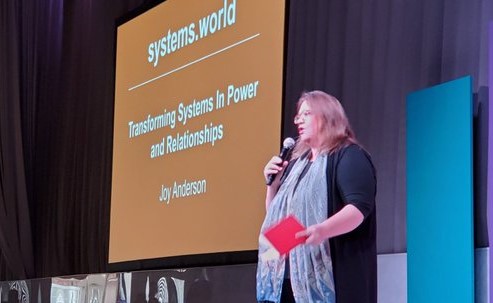

More opening remarks. Grateful-to-have sponsor shout outs. A spiritual and thoughtful land acknowledgement. Then a “narrative healing” dance and spoken word performance. And facilitated discussions on subjects such as Afrofuturism, resistance, rematriation movements, inclusive feminism, what a decolonized economy might look like. With everyone invited to participate, you never knew what would happen or come out of it. Aha moments and learnings collectively generated—versus pipeline fed.

Someone quoted Tracee Ellis Ross, an American Black actress and activist, and I wrote it down: “I am learning everyday to allow the space between where I am and where I want to be inspire me and not terrify me.”

During breaks, I took in the art show in the main hall and snapped a few pictures of the art in the hall.

Later that afternoon, I Lyft-ed over to a solidarity concert held at the Paradise Theatre in support of the Wet’suwe’ten land rights standoff (remember that?). I heard a line up of amazing emerging female musicians including Stones, Lavender Bruisers, Mimi O’Bonsawin, Caroline Brooks (Good Lovelies), Skye Wallace, Tange and Moscow Apartment. I loved one song by the band Tange so much, I listened to it ten times when I got home and licensed it to accompany our International Women’s Day slide show.

A Snippet of a performance by TANGE at Toronto’s 2020 International Women’s Day fundraising concert for the Wet’suwet’en Legal Fund and Climate Justice Toronto. at the Paradise Theatre.

LiisBeth Media’s IWD 2020 Roundup of Events Attended-Live.

I must have been swept away by the concert. Because I made no notes. Not even musical ones.

I turned the page.

More scribblings and quotes, this time from a fundraiser for The Redwood (A women’s shelter) few days later. They screened “The Feminist in Cell Block Y”, an incredible documentary about a convicted felon who taught feminist literature to fellow inmates in an all-male prison in Soledad, California. I wrote down my impressions of seeing the men read, out loud, passages from bell hooks’ books. I copied notes from the facilitator’s flip chart in the film — how patriarchy incites violence, rape culture, crime and anger because it’s the only way most men can live up to and rail against patriarchal ideals of masculinity.

After the screening, a panel of filmmaker and grassroots activists gathered on stage to share their impressions of the film with the 200+ plus who attended.

I recalled sharing a link to the film afterward on social media. And going for food and drinks with my partner to talk about our experience.

I could have spent hours flipping through this notebook.

Instead, I spent time thinking about how these gatherings compare to their ZOOM replicant.

Why can I remember so much about in-person gatherings whereas with online gatherings and events, I struggle to remember anything at all? Who was there? What season –or even day was it? Can technology mediated spaces even can create memories or lasting impact?

Over the summer, I engaged in oodles of online events. Gatherings of five to 500. Breakout rooms. Whiteboards. Cool speakers. Yet, when I try to recall them, it’s like they never happened. Ideas and conversations , unanchored, rise and evaporate in minutes. How can I retrieve and build on what I took with me without the aid of sensory clues? Stains on my notebook caused by a seatmate’s wandering elbow?

I realized I not only desperately miss these feminist and embodied gatherings; They served as essential wayfinding experiences for someone on a transformational journey.

To do their magic, they actually require all this: Subversive, stark gathering spaces with uncomfortable seats. Being in full-bodied community with people. Craft tables selling feminist art. Zines. Screen-printed patches and pins for sale. Challenging large scale art works to be experienced, not just viewed (at one event, a large pink-and-red vagina made of silk veils and pillows that you could walk through; at another, a re-interpreted Judy Chicago table setting which you could touch). Hand-illustrated name tags with pronouns. Music by emerging female, trans or queer talent who don’t get enough stage time in mainstream venues. The extraordinary care paid to creating accessible, safe spaces where we could have brave, vulnerable conversations with strangers. Seminars and performances coming alive with diverse, fierce, feminist grassroots educators, questioners, creators, writers and entrepreneurs aged 16-93.

In these spaces, even on days when it feels as though there is a hole at the bottom of my cup, I could always count on an upcoming opportunity to refill it from a flowing fountain of rebellion, reflexive learning, camaraderie and inspiration.

Ultimately, it this deep respect for the incredible work of revolutionary feminists creating such spaces that inspires the work we do at LiisBeth Media and, more recently, the Feminist Enterprise Commons.

Much has been written about how the pandemic has surfaced and re-confirmed the nature and depth of the mess we have made of the world we live in.

It has also, I hope, irrevocably, lifted our understanding of what it means to be human and tightly fastened the insight that that only humans—not technology—can truly, meaningfully transform the world we live in.

Sadly, we won’t be able to be together like ways I described again for a long time. Realizing this makes me sad—and question my own stamina to do this work in the absence of these vital re-fuelling stations.

But giving up is not a really a choice.

And surely, feminist gatherings and events will comeback soon.

Opening up to the last page of this notebook, I hastily over-wrote; If mushrooms and wild flowers can grow strong in mud, shit and decay, then so can I. Underline.

Publisher’s note: If you are looking for meaningful feminist conversations online, consider The Feminist Enterprise Commons (operated by LiisBeth Media, Canadian based), The Continuum Collective (U.S. based, founded by Jillian Foster) and PowerBitches Gather (U.S. Based, founded by Rachel Hills).

Related Reading

State of the Art: Making Room and Income for Women in Art

Meet six incredible feminist art equity and gender justice activists who are reimagining the art market.

The Art of Change

A feminist collective comes together to bring real talk to the art world.

Ilene Sova: A Woman of Action

“As someone who disagrees with how the system works today, and as a feminist activist, I wake up each day asking myself what will I actually do to change it?”-Ilene Sova, Founder of FAC